The 1968 Olympics

Avery Brundage to IOC at opening session, 1968:

"We live today in an uneasy and even rebellious world, a world marked by injustice, aggression, demonstrations, disorder, turmoil, violence and war, against which all civilized persons rebel, but this is no reason to destroy the nucleus of of international cooperation and goodwill we have created in the Olympic movement....You don't find hippies, yippies or beatniks on sports grounds."

Pedro Ramírez Vázquez, architect and chair of the Mexico City Olympic organizing committee: “People already know all about the folkloric Mexico, the scenic Mexico and its ancient origins…yet no one knows the high levels of efficiency and technical expertise that Mexico has achieved. This is the Mexico that we wish to demonstrate through the medium of the Olympics....The records fade away, but the image of a country does not.”

This is true in both good and bad ways: Mexico very badly wants to make its case for inclusion among the world's successful nations, and in pursuit of this goal it treats some of its people very badly.

Olympics Cultural festival runs for 9 months before Games begin, staging over 1500 events and drawing on Mexican artists, intellectuals, poets, writers. Light show at Aztec pyramids in Mexico City, with Charlton Heston and Vincent Price narrating for visitors. It is the first Olympics to be shown in color, and the first with drug- and sex-testing for competitors.

As part of this, visual artists from around the world build the Route of Friendship (Ruta de la Amistad), hoping to both send a message of peace and beautify the city. It remains a tourist attraction.

Less appealingly, residents of poorer areas are told to do their part by being handed pink, purple, and yellow paint and being instructed to "get to work." Volunteers, translators, and assistants are disproportionately upper middle-class and light-skinned. The slogan "Everything Is Possible in Peace" is everywhere, as are dove images like the ones above and below.

Student protestors detourn these slogans for their own purposes, awarding their country a “Gold Medal for Repression” and “We Don’t want the Olympics, we want a revolution” They say, "We weren’t against the Olympics as a sports event, but we were against what the Games represented economically. We’re a very poor country, and the Olympics meant an irreparable drain on Mexico’s economic resources…"

The repression causes some upset, but IOC head Avery Brundage remarks, “I was at the ballet last night.”

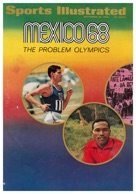

Trying to be sympathetic, John Underwood of Sports Illustrated writes this racist description of the country:

It is not true that Mexicans are lazy, but they do have great patience in getting things done. Conservative Mexican thieves are known to risk capture by taking the time to remove the radio without stealing the car. But the Mexicans can also strike with inspirational fire when there is a chance to do something bold and fresh.

Mexico's particular troubles begin with geography. Mexico City is 7,349 feet above the sea and places such demands on a man's lung capacity that at least one alarmist has predicted runners will die during the Games….Troubles move from there to the stereotype of the Mexican peasant, slumped against the wall, sombrero down to shield his eyes from the work left undone. The Japanese, miffed that they had not been consulted on how to shape up Mexico City construction, predicted an Olympic doomsday. A European said flatly, "These people [the Mexicans] can't do it." Hardly anyone was willing to believe that the Mexicans were actually working around the clock, by sun and by floodlight, to beat the deadline.

Then there was the question of Mexico's smoldering young activists. They don't like President Gustavo Diaz Ordaz' government, and they are trying to bring it down. As activists they are no different from the young at Berkeley or Columbia. That is to say, some of them are true idealists, and some are what Daniel J. Boorstin has termed the New Barbarians. They are unable to see any long-range good—economic stimulation, national pride—coming from a $150 million Olympic expenditure.