The Cristero Revolt

This uprising, lasting from 1926-29, by Roman Catholics responded to both local and national anti-clerical measures (see other links in this section) and a general sense of estrangement from the tone of contemporary Mexican life (radical murals, public education, agricultural commercialization). Historian Matthew Butler, in Popular Piety and Political Identity in Mexico's Cristero Rebellion, argues that popular support for the revolt was strongest where orthodox forms of Catholicism were most tied to the community, where priestly influence was greatest, and where revolutionary reforms had made the fewest inroads. These people felt especially intellectually and emotionally attached to the Church, sacraments, and priests and threatened by the state, and thus they fought to defend the ways of life to which they were accustomed.

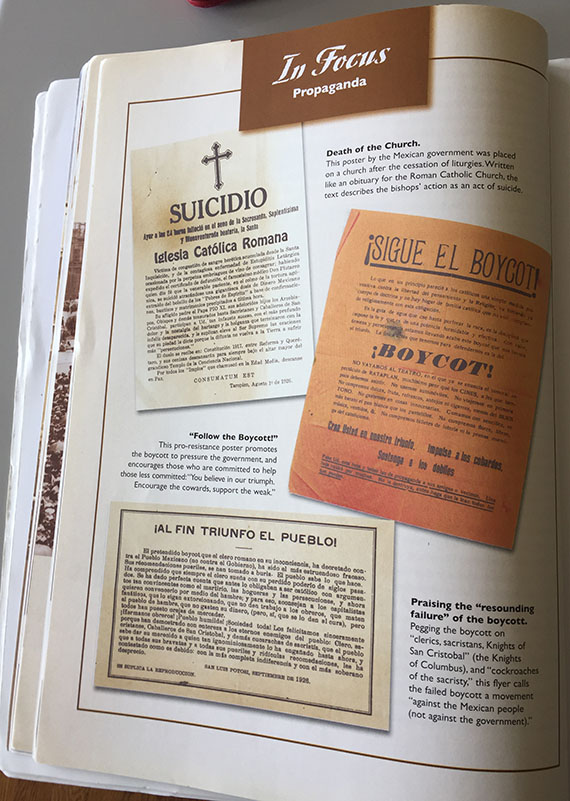

The conflict comes seemingly out of nowhere. In February 1926, protesting Calles' new enforcement of the constitution, the newspaper El Universal runs a 9-year-old interview with the Archbishop of Mexico City, José Mora y del Río, in which he criticizes articles 3, 5, 27, and 130 of the constitution for their antireligious comment---but as if the interview had just happened.In response to what seems like a new wave of clerical complaints about what had been law for 9 years, Calles dismisses the pujidos (bitching) of the overly pious and says he "strongly wishes" to see the prejudices of the past "liquidated." Consul General Arturo Elías subsequently writes to the New York Times that the clergy "have consistently fought the constituted authorities, neglected their spiritual mission, and been the uncompromising foe of all progress" and thus deserve harsh treatment. In early July, the government makes public a decree signed by Calles in June firmly applying the 1917 constitution's provisions limiting religion and spelling out penalties for infractions. Among other things, the government deports foreign priests and nuns; limits the number of priests in each state; closes all church schools, monasteries, convents; and forces priests in charge of churches to register with the government. Calles claims that the law does not discriminate because it applies to ALL religions, but there are very few non-Catholics in the country, and bans on celibacy and monastic life apply only to Catholics. The Pope denounces the conduct of the Mexican government in the encyclical "Iniquis Afflictisque" ["On the Persecution of the Church in Mexico"] 1926. Gov't then sponsors creation of a national church under the government’s control. It does not recognize the Vatican and declares celibacy immoral and illegal. It also uses a corn tortilla instead of a wheat communion wafer and mescal in place of wine. After the government awards it a church building on a main street, the archbishop of Mexico City bans Catholics from entering the building.

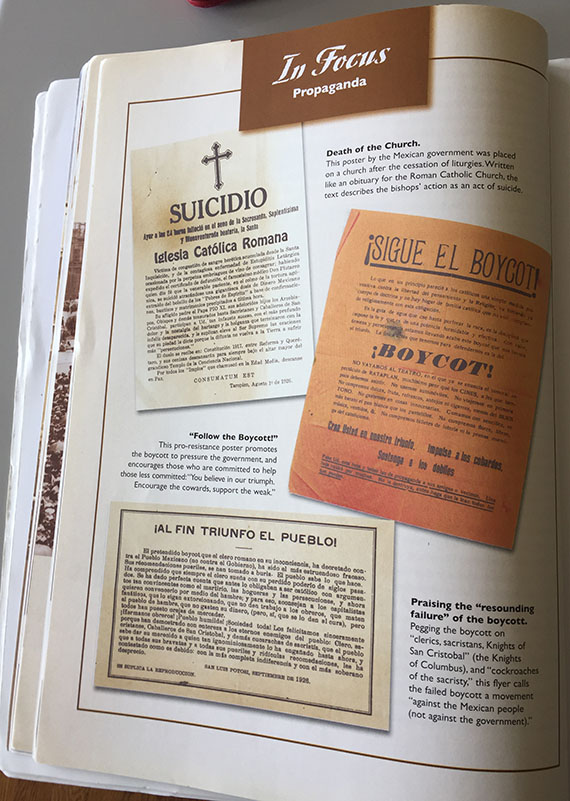

In response, perceiving a sudden increase in enforcement, the bishops go into permanent secret session. They are particularly worried about section 19 of the decree, which requires priests who are in charge of churches to register with the government, which could, they fear, allow the government rather than the church to appoint and dismiss priests at will. The majority favors waiting to see what happens and trying to negotiate some sort of compromise. More radical elements want the church to resist, immediately and firmly.The more radical viewpoint wins, the Archbishop of Mexico proclaiming that these anticlerical measures prevent Catholics from accepting the Constitution, so they must go on strike unless the decree is repealed before it goes into effect on on Aug. 1; Catholics are urged to refuse to attend movies, ride street cars, or work in or send their children to secular schools, and churches will hold no mass, baptize no babies, and administer no last rites. In preparation for this, Time magazine reports, Archbishop José Mora y del Río nearly faints after putting on a business suit and derby hat to conceal his priestly vestments and confirming 3000 Catholics in one day, then regaining consciousness and continuing to perform confirmations until the stroke of midnight on July 31, when the boycott takes effect. A government official responds by standing outside the cathedral and telling everyone entering that they must be vaccinated before doing so. He then "jabbed often, jabbed deep" without sterilizing or changing the needle.

The economic response dissipates by October, but the church boycott on ceremonies lasts THREE YEARS. The government arrests the leaders who make this decision and throws them in military prison for a month.

The uprising, which breaks out in September, results from the government's reactions to the bishops' decision.

Calles does not countenance any challenges to his power. He calls the conflict "the struggle of darkness against light" and says that "the hour is coming in which the final battle will be fought." He gives the church two options: "the law or guns" (think here of Porfirio Díaz). Starting in August, no mass is celebrated around the country, and local citizens' committees take over the churches. The government bans private worship.

The uprising, which breaks out in September, results from the government's reactions to the bishops' decision.

Calles does not countenance any challenges to his power. He calls the conflict "the struggle of darkness against light" and says that "the hour is coming in which the final battle will be fought." He gives the church two options: "the law or guns" (think here of Porfirio Díaz). Starting in August, no mass is celebrated around the country, and local citizens' committees take over the churches. The government bans private worship.Unsurprisingly, conflict breaks out.

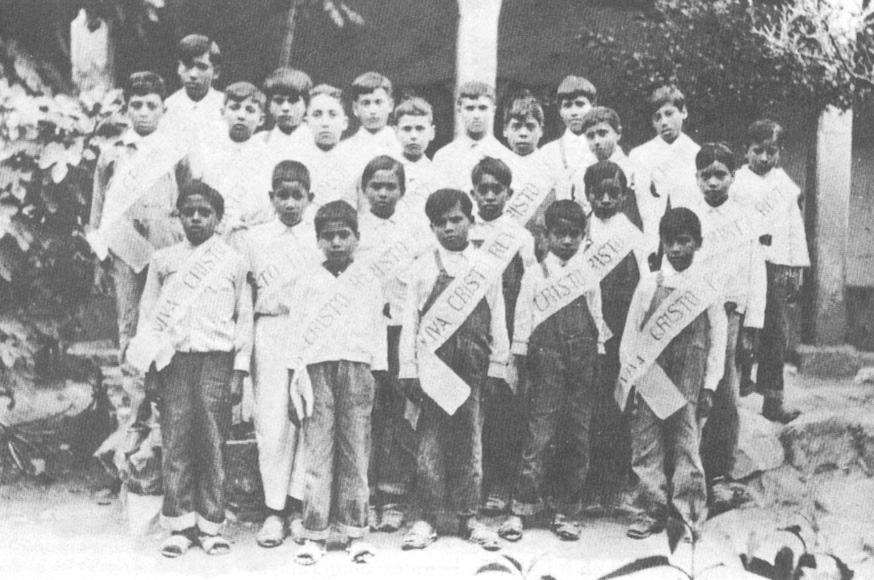

In Mexico City, police fire on communicants who refuse to leave the San Rafael church, wounding nine, and women throw stones at them from the roof. A crowd of "irate Catholics" attacks the Attorney General as he tries to close the Santa Catarina church. Street fighting erupts in Guadalajara, leaving many dead and wounded and hundreds jailed. In Zacatecas, Father Luis Batí Sáinz is killed, and later named a saint, for resisting. In 2000, Pope John Paul II canonizes 25 such saints from the Cristero Revolt.At first, the government mocks the rebels. One politician reads out a list of the skirmishes in Congress and remarks, "they do not know how to carry out a revolution. They should ask us about it. We could give them revolution classes." But this resistance eventually coalesces into another civil war. The National League for Defense of Religious liberty, as usual in such times of turmoil, publishes its manifesto. Called A la Nación, it calls for a unified rebellion by next January. Cristero activist Luis Gutiérrez explains that "the government takes away everything from us, our corn, our pastures, our animals, and, if this were not enough, it also wants us to live like beasts, without religion or God. But they will not see this last thing happen....Death to the government!" By January 1927, rebellion is indeed flaring nationwide. The federal army has 70-80,000 troops, the Cristeros perhaps 20,000 men by July and 50,000 by 1929. Federal troops can fire 250 rounds per soldier per day, the Cristeros 20.

Cristeros celebrating a mass in the field

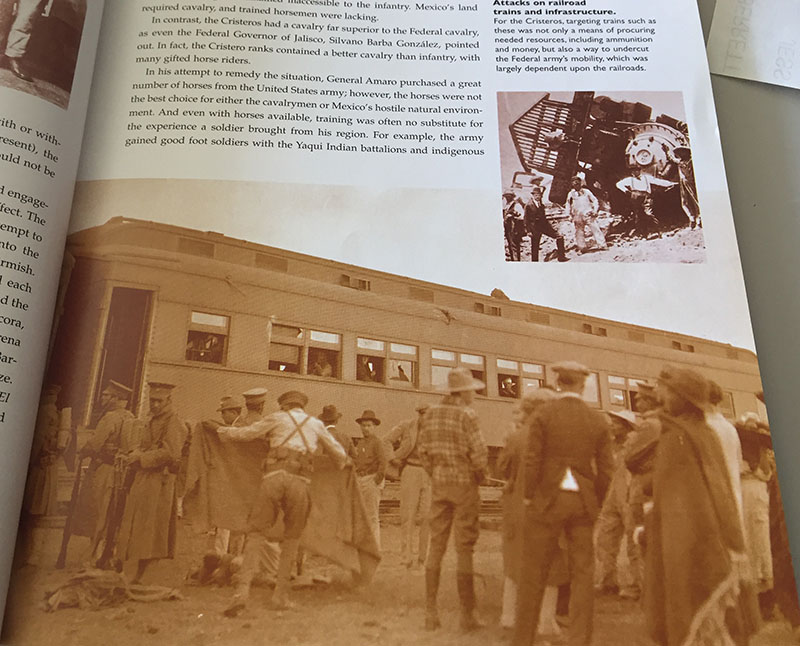

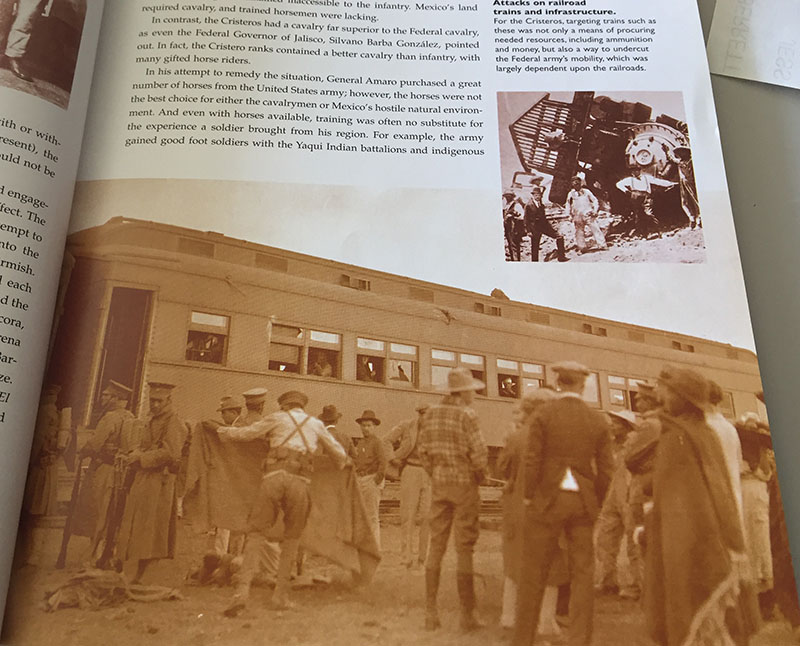

Guerrillas blow up government schools, murder teachers, and blow up trains.

The government tries to kill a priest for every dead teacher,

a Priest being executed

a Priest being executed

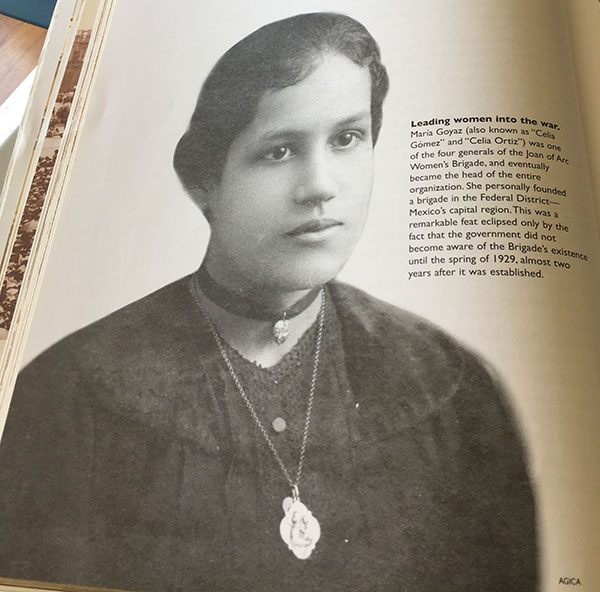

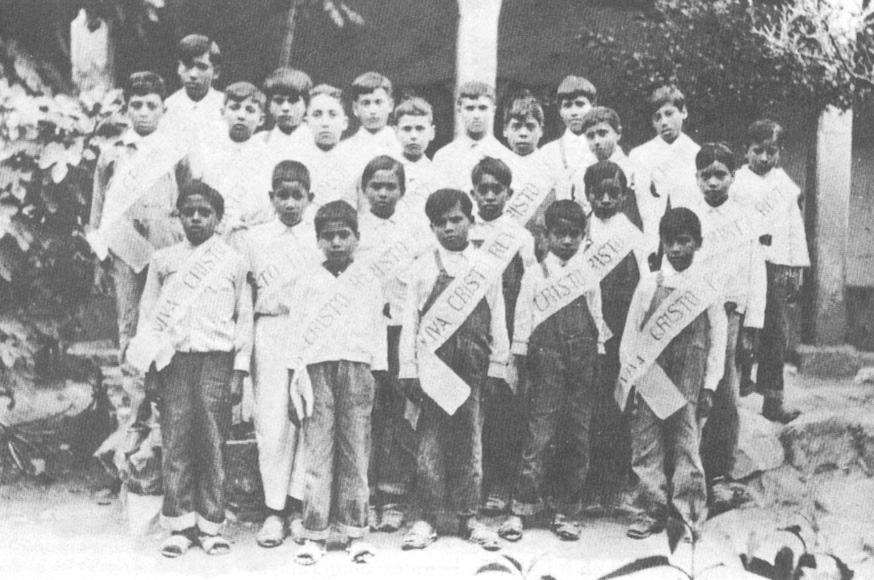

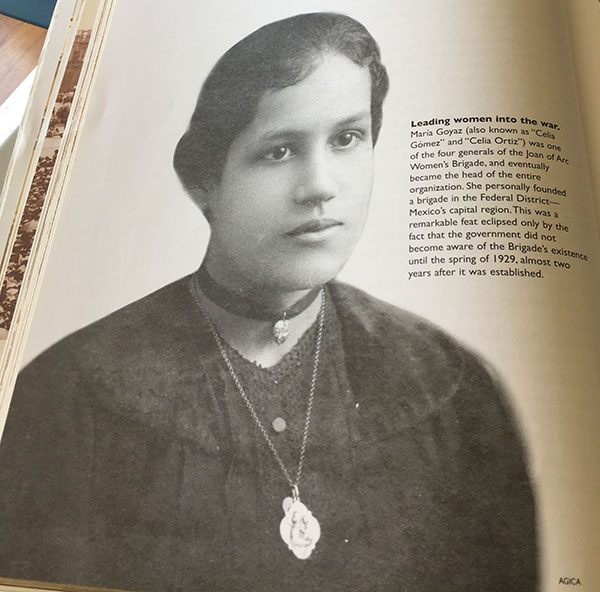

has children throw rocks through stained-glass windows, loots churches and turns them into stables; radicals bomb the shrine of the Virgin of Guadalupe and attempt to assassinate the Archbishop. Over the summer, the rebels hire General Enrique Gorostieta, a veteran of the revolution who had fought for Madero and later against Zapata, to professionalize the army. Gorostieta was a mercenary, according to historian Jean Meyer, rather than a true believer. He hates Calles, and some suspect that he wishes to follow in the tradition of Santa Anna and become President.Women play important roles in the revolt as spies, suppliers, and organizers.

Women's Brigade member Toñita Castillo, second from left, in the field with her mother (at left).In June, they form the Joan of Arc Women's Brigade, with regiments of 650 women each.

Women's Brigade member Toñita Castillo, second from left, in the field with her mother (at left).In June, they form the Joan of Arc Women's Brigade, with regiments of 650 women each.

Its primary responsibility is to issue propaganda, get money, deliver ammunition to the men, often in secret, and care for the wounded, but some also design explosives and teach demolition. More than 25,000 women join by war's end.

The Cristeros enjoy military success through early 1929, winning several major battles, but they lack resources and outside support (the US government supports the Mexican federal government). Their leaders understand that they cannot fight indefinitely. The conflict is eventually settled with compromises on both sides: priests recognized by the church will register with the government (rather than the government recognizing priests on its own), no religious education in schools, and rebels will receive amnesty; the church will be protected and can offer education within its doors. It resumes holding services. General Gorostieta is killed in an ambush in early June, removing one major obstacle to peace. Three weeks later, the two sides lay down their arms.

About 90,000 soldiers die, with the total death toll including civilians estimated at 200,000. Agricultural production, which had increased 60% 1921-26, drops 38% 1926-29. Corn production drops 25% and bean production 50%.Not all religious figures are satisfied: the papacy issues two other encyclicals protesting continuing mistreatment of the church in Mexico: "Acerba Animi" in 1932 and "Firmissimam Constantiamque" (1937)The legacy of the Cristero Revolt, according to historian David Bailey in Viva Cristo Rey!, is that "in the terms on which the religious conflict was joined, the revolution won. The possibility of formal Catholic leadership in Mexico...was gone, at least for a long time. The anticlerical laws remained and in fact were made more harsh in the few years following the 1929 truce." But he adds that religion "did not lose," because "unofficial toleration" became the law of the land again, and so the church resumed its mission. Most citizens "wanted Catholicism to remain a part of their private lives, and laws, it turned out, were not an insurmountable obstacle to this."

The uprising, which breaks out in September, results from the government's reactions to the bishops' decision.

Calles does not countenance any challenges to his power. He calls the conflict "the struggle of darkness against light" and says that "the hour is coming in which the final battle will be fought." He gives the church two options: "the law or guns" (think here of Porfirio Díaz). Starting in August, no mass is celebrated around the country, and local citizens' committees take over the churches. The government bans private worship.

The uprising, which breaks out in September, results from the government's reactions to the bishops' decision.

Calles does not countenance any challenges to his power. He calls the conflict "the struggle of darkness against light" and says that "the hour is coming in which the final battle will be fought." He gives the church two options: "the law or guns" (think here of Porfirio Díaz). Starting in August, no mass is celebrated around the country, and local citizens' committees take over the churches. The government bans private worship.

a Priest being executed

a Priest being executed Women's Brigade member Toñita Castillo, second from left, in the field with her mother (at left).In June, they form the Joan of Arc Women's Brigade, with regiments of 650 women each.

Women's Brigade member Toñita Castillo, second from left, in the field with her mother (at left).In June, they form the Joan of Arc Women's Brigade, with regiments of 650 women each.