summary of mid-century economic progress

(excerpted from Foster, Brief

History of Mexico, 196-201).

To what

extent does the government change its ideals in the service of economic growth,

and to what extent does it violate what the Revolution had been fought for?

business/industrial climate improves

Government ideology changes focus. In his inauguration in 1940, President Ávila Camacho, "elected" with 94% of the vote, proclaims that the Revolution has pretty much succeeded: "everybody will reach the conclusion that the Mexican Revolution has been a social movement guided by justice alone, which is now historical. It has achieved for a people the essentials of living." So it is therefore time to work on economic growth. The next two PRI presidents will win 78% and 74% of the vote, though in 1952, liberal 1930s president Lázaro Cárdenas, dissatisfied with the PRI's procedures, challenges it to open the process so that more members of the party are involved in choosing the next leader. This does not happen, but Cárdenas is satisfied when the next president proves to be more liberal. For its part, the "opposition" party, the PAN, debates whether or not it should even bother to run candidates, since its "existence" as an alternative legitimizes the PRI's rule. This period marks "a long crossing of the desert," a party historian writes.

Mexico receives an economic boost from WWII (see chart below); major idea is to protect domestic manufacturing from foreign control and allow it to develop in Mexican hands. After Pearl Harbor, the President says, "our industries and our agriculture must also intensify their labors. Since the circumstances do not obligate us to outright belligerent acts, our fight will not be in the trenches, but in the factories and in the furrows. We must develop the capacity of our economy and strengthen the productivity of our commerce so that all these efforts will be directed toward one end: to contribute to the security of the Americas with order and with work....In the present condition of emergency, patriotism must be placed above everything else. America is in danger. Mexico is in danger, therefore, no effort is too small and no risk is too great. Workers, peasants, professionals, the poor, both industrial and commercial classes, we must all rally ourselves around the glorious flag of the Republic."

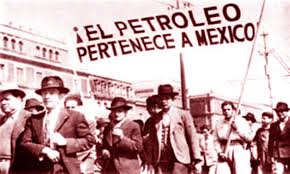

"51% rule," enacted 1944, says that Mexican investors must own more than half of every company. Industrial sector grows an average of 10%/year, 1940-45; 7.3%/year, 1950s. US companies such as Coke, Pepsi, GM, Ford, Dow Chemical, Sears, John Deere make so much money that they do not complain. Mexican raw materials supply 40% of US war industry. Blend of public and private ownership; government owns all or most of oil (Pemex, a contraction of Petróleo Mexico), electricity, insecticide, fertilizer industries, and controls prices to fuel economy. Mexico is self-sufficient in (has no need to import) iron, oil, and steel by 1964. Electrical capacity up 20%, 1940-46, and triples by 1952.

|

|

Is this the fulfillment of the revolution, or its betrayal? Note that much of this growth trickles down. According to historian John Womack, "real GNP expanded through the decade by 70 percent, while the population expanded by 27 percent. The real national income increased through the decade by almost a half."

On the other hand,

Mexican economist

Daniel Cosío Villegas writes an article, "The Crisis of Mexico," in 1946,

arguing that the revolution is dead, and its great principles have been corrupted

or abandoned. Other evidence: there are huge public works programs (see below), such as National University of Mexico, dedicated 1952 and looks great (and what do you see in the photo?), but it has very few books on the shelves; many inequalities remain (c. 1/3 of children ages 6-14 are in school, and half of them are literate; Mexico City population rises 50% 1952-58, and poverty is high).

year |

maize |

cotton |

steel |

zinc |

oil |

1930 |

1.377M metric tons |

38,000 metric tons |

103,000 tons |

124,000 metric tons |

39.5M barrels |

1940 |

1.64M |

65,000 |

149,600 |

115,000 |

44.4M |

1950 |

3.12M |

260,000 |

332,600 |

223,000 |

73.9M |

1960 |

5.4M |

470,000 |

1.49M |

262,000 |

108.8M |

1970 |

9M |

398,000 |

3.88M |

266,000 |

177.6M |

1980 |

11M |

340,000 |

7.3M |

236,000 |

708.9M |

(a metric ton is 1000Kg, or about 2200 lbs.)

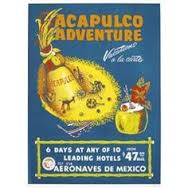

focus on infrastructure: dams, electrical plants, oil pipelines and refineries, 15,000 mi. of highways by 1957 (Pan-American Highway, linking US and Guatemala, completed 1950; Nogales-Guadalajara route added 1954). Airports, hotels (1600 rooms in Mexico City, 1935; 3600, 1942; number of rooms doubles, 1954-62) and highways aid growth of tourism industry (90,000 airline passengers, 1940; 1 million, 1952); new Acapulco airport makes it a popular tourist destination. Historic pre-Columbian sites (Monte Albán, Teotihuacán, Mayan cities) are all made heritage sites to attract tourists. Also connected to Cuban revolution of 1956, which ends US tourism to Cuba after 1959: in 1928, c. 12,500 tourists visit Mexico; 80,000 visit Cuba. Tourism is low at first (8000 visitors, 1920), so government creates a tourism bureau, 1928, that places ads in US papers and tries to get stories written extolling tourism. Tourism triples, 1939 (c.139,000 visitors)-1951 (c.390,000, 1951), gross receipts up 5x over that period. 550,000 US vistors, 1955, 2M total, 1972. Mexico is now the #1 tourist spot in Latin America. Former President Miguel Alemán serves as Director General of the National Tourism commission, 1958-83. Foreign tourism increases 12% annually, 1950-72, more than double the rate of the economy as a whole. Tourism receipts, 1972, are $1.7B, more than all exports bring in.

The focus on tourism, and Acapulco in particular, emphasizes the success of the PRI's programs. It is also low-cost--does not require factories or factory-level investments. Historians call this "revolutionary capitalism," allowing the state and revolutionary elites a means to participate in a modern capitalist economy. "The material benefits of the Mexican wartime economy accelerated the expansion of the country's middle class and ballooned the affluence of Mexican elites, allowing an increasing number of Mexicans the means to participate in the lure of Acapulco. Furthermore, famous movie actors, well-known writers, eminent artists and the socially prominent made Acapulco their playground, adding a unique social patina to the port city....As a budding, attractive opulent spot for influential Mexicans--as well as foreign tourists--Acapulco invited intrigue, greed, corruption, and a deepening commercialization of Mexico's 'official culture.'...Tourists eager to experience 'Mexican culture' found an infrastructure to provide it (government-regulated), ready-made availability (licensed packaged tours), accessibility (state-approved multilingual guides), and the exotically different...usually delivered by a smiling staff dressed in 'typically Mexican' uniforms of one type or another, eager to please."

--Alex Saragoza, "The Selling of Mexico: Tourism and the State, 1929-1952," in Fragments of a Golden Age: The Politics of Culture in Mexico Since 1940, ed. Gilbert Joseph, Anne Rubinstein, and Eric Zolov

|

|

|

|

|

|

(from Dina Berger, The Development of Mexico's Tourism Industry: Pyramids

by Day, Martinis by Night;

William Bryan,

"History

and

Development

of

Tourism

in

Mexico.")

Irrigation, better seeds, and land

reclamation help increase corn yield from 300kg/hectare

to 1300. (Think back to the Porfirio Díaz administration as well.)

labor policies

generally a compromise between anti-labor policies in order to accommodate business growth and honoring the goals of the Revolution. (Labor unions go along with this to some degree: main union's slogan changes from "For a society without classes" to "For the emancipation of Mexico" in 1947.) Per capita income is 325 pesos, 1940; 838 pesos, 1946, but not spread evenly. Government declares most strikes illegal; a Supreme Court decision in 1948 briefly makes it more or less impossible to strike by declaring all strikes illegal when there is a contract in effect. Taxi drivers strike, 1950, but police raid union headquarters and beat leaders, killing two. Several massacres of strikers by the military, including Oaxaca, 1952, and Mexico City. When railroad workers strike, 1959, after initial gov't attempts to settle the strike, military raids union hall, accusing leaders of being Communist puppets, and union leader Demetrio Vallejo sentenced to 16 years in prison.

There is a minimum wage, and social security (along with health care!) for workers begins, 1943. All workers insured, mid-50s. But the real wage of workers is less in 1960 than in 1940, even as productivity doubles. Less than 12 M acres of land redistributed, but all go to private farms rather than ejidos. Ejidos not quite as productive as commercial farms: 43% of crop land but produce only 40% of crop value. (Is this due to low productivity, or the fact that the government did not supply ejidos equally? They get only 20% of tractors, and much of the best land remains in private hands.) Agriculture is 10% of GDP (gross domestic product, "the total market values of goods and services produced by workers and capital within a nation's borders during a given period") 1940, 5% 1973.

education and women's rights

anti-clerical tones of 20s, 30s (recall Cristero Revolt and Socialist ABCs) are dropped; illiteracy drops from 58% to less than 43%; still, less than 1% of rural children finish 6th grade; women get the right to vote, 1954; Mexico passes Equal Rights Amendment, 1974 (for comparison, it is proposed in US Congress from 1923 on, finally passes Congress, 1972, but falls three votes short of ratification by the states and is never passed). PRI wins 98% of all mayoral and congressional elections, 1946-73.