By Sam Quinones

Foreign Policy magazine

March/April 2009

Mexico’s hillbilly drug smugglers have morphed into a raging insurgency.

Violence claimed more lives there last year alone than all the Americans killed

in the war in Iraq. And there’s no end in sight.

Tomas Bravo / Reuters

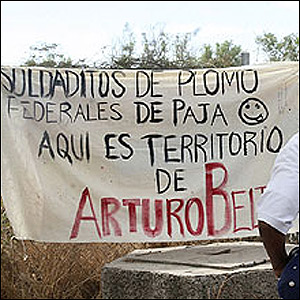

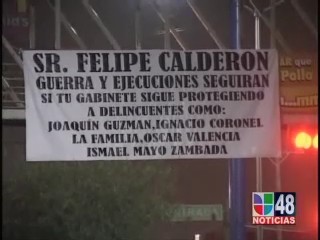

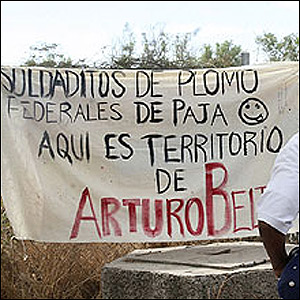

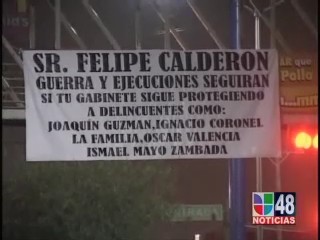

What I remember most about my return to Mexico last year are the narcomantas. At least that’s what everyone called them: “drug banners.” Perhaps a dozen feet long and several feet high, they were hung in parks and plazas around Monterrey. Their messages were hand-painted in black block letters. They all said virtually the same thing, even misspelling the same name in the same way. Similar banners appeared in eight other Mexican cities that day—Aug. 26, 2008.

The banners were likely the work of the Gulf drug cartel, one of the biggest drug gangs in Mexico. Its rival from the Pacific Coast, the Sinaloa cartel, had moved into Gulf turf near Texas, and now the groups were fighting a propaganda war as well as an escalating gun battle. One banner accused the purported leader of the Sinaloa cartel, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera, of being protected by Mexican President Felipe Calderón and the army. After some time, the city’s police showed up politely to take the banners down.

I’d recently lived in Mexico for a decade, but I’d never seen anything like this. I left in 2004—as it turned out, just a year before Mexico’s long-running trouble with drug gangs took a dark new turn for the worse. Monterrey was the safest region in the country when I lived there, thanks to its robust economy and the sturdy social control of an industrial elite. The narcobanners were a chilling reminder of how openly and brazenly the drug gangs now operate in Mexico, and how little they fear the police and government.

That week in Monterrey, newspapers reported, Mexico clocked 167 drug-related murders. When I lived there, they didn’t have to measure murder by the week. There were only about a thousand drug-related killings annually. The Mexico I returned to in 2008 would end that year with a body count of more than 5,300 dead. That’s almost double the death toll from the year before—and more than all the U.S. troops killed in Iraq since that war began.

But it wasn’t just the amount of killing that shocked me. When I lived in Mexico, the occasional gang member would turn up executed, maybe with duct-taped hands, rolled in a carpet, and dropped in an alley. But Mexico’s newspapers itemized a different kind of slaughter last August: Twenty-four of the week’s 167 dead were cops, 21 were decapitated, and 30 showed signs of torture. Campesinos found a pile of 12 more headless bodies in the Yucatán. Four more decapitated corpses were found in Tijuana, the same city where barrels of acid containing human remains were later placed in front of a seafood restaurant. A couple of weeks later, someone threw two hand grenades into an Independence Day celebration in Morelia, killing eight and injuring dozens more. And at any time, you could find YouTube videos of Mexican gangs executing their rivals—an eerie reminder of, and possibly a lesson learned from, al Qaeda in Iraq.

Then there are the guns. When I lived in Mexico, its cartels were content with assault rifles and large-caliber pistols, mostly bought at American gun shops. Now, Mexican authorities are finding arsenals that would have been incomprehensible in the Mexico I knew. The former U.S. drug czar, Gen. Barry McCaffrey, was in Mexico not long ago, and this is what he found:

The outgunned Mexican law enforcement authorities face armed criminal attacks from platoon-sized units employing night vision goggles, electronic intercept collection, encrypted communications, fairly sophisticated information operations, sea-going submersibles, helicopters and modern transport aviation, automatic weapons, RPG’s, Anti-Tank 66 mm rockets, mines and booby traps, heavy machine guns, 50 [caliber] sniper rifles, massive use of military hand grenades, and the most modern models of 40mm grenade machine guns.

These are the weapons the drug gangs are now turning against the Mexican government as Calderón escalates the war against the cartels.

Mexico’s surge in gang violence has been accompanied by a similar spike in kidnapping. This old problem, once confined to certain unstable regions, is now a nationwide crisis. While I was in Monterrey, the supervisor of the city’s office of the AFI—Mexico’s FBI—was charged with running a kidnapping ring. The son of a Mexico City sporting-goods magnate was recently kidnapped and killed. Newspapers reported that women in San Pedro, once one of Mexico’s safest cities, now take classes in surviving abductions.

All of this is taking a toll on Mexicans who had been insulated from the country’s drug violence. Elites are retreating to bunkered lives behind video cameras and security gates. Others are fleeing for places like San Antonio and McAllen, Texas. Among them is the president of Mexico’s prominent Grupo Reforma chain of newspapers. My week in Mexico last August ended with countrywide marches of people dressed in white, holding candles and demanding an end to the violence.

In Monterrey, most were from Mexico’s middle and upper classes, people who view protests as the province of workers and radicals. In all my time in the country, I had seen such people turn to protest only once: during the 1994 peso crisis, when Mexico was on the brink of economic collapse.

I’ve traveled through most of Mexico’s 31 states. I’ve written two books about the country. And yet I now struggle to recognize the place. Mexico is wracked by a criminal-capitalist insurgency. It is fighting for its life. And most Americans seem to have no idea what’s happening right next door.

What happened in the four years I was gone? Fueled by American demand, dope was always there, of course. So was a surplus of weapons and gangs to use them. When I lived in Mexico, drug violence was a story, but not the story it is today.

I remember grander concerns back then: Mexico peacefully shedding 70 years of one-party authoritarian rule and dreaming of becoming a stable and prosperous democracy. But Mexico’s one-party state, led by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), gave way to the control of a few parties, which were as inert and unaccountable as their authoritarian forebears. They bickered about minutiae in congress, and the hoped-for reforms didn’t come. The PRI’s centralized political control was gone, but nothing effectively took its place. This vacuum unleashed new opportunities for criminality, and Mexico’s institutions weren’t up to the new threats that emerged.

Most of the cartels that now battle for drug routes into the United States emerged in the Pacific Coast state of Sinaloa—a mid-sized Mexican state with an outsized drug problem. Mexican drug smuggling began primarily among rural and mountain people from lawless villages who are known to be especially bronco—wild. Marijuana and opium poppies grow easily in Sinaloa’s hills. A narcoculture has evolved there, venerating smugglers and their swaggering hillbilly style, called buchon. Hicks became heroes. They moved into wealthy neighborhoods and fired guns in the air at parties. Bands sing their exploits; college kids know how they died. Sinaloa is that rare place where townies emulate hayseeds, and youths yearn to join their ranks.

These renegades have grown into a national security threat since I’ve been away from Mexico. One reason is that regional drug markets have changed a lot in the past few years. The Colombian government grew more successful against narcotraffickers who had taken over large parts of Colombia. Enforcement in the Caribbean also improved. Once-settled Mexican smuggling routes suddenly became the best way to move dope through Latin America and into the United States. Those routes were now up for grabs, and much more was at stake. Old gang enmities exploded. Mexico’s cartels could not let their rivals take over new drug routes for fear they’d grow stronger. The gangs began vying for turf in an increasingly savage war with a constantly shifting front: Acapulco, Monterrey, Tijuana, Juárez, Nogales, and of course Sinaloa.

With war raging between Mexico’s narcogangs, and with plenty of cash available from drug sales to Americans—$25 billion a year, by one reliable estimate—cartel gunmen began to grow discontented with the limited selection of arms found in the thousands of gun stores along the southern U.S. border. Instead, they have sought out—and acquired—the world’s fiercest weaponry. Today, hillbilly pistoleros are showing signs of becoming modern paramilitaries.

Mexico’s gangs had the means and motive to create upheaval, and in Mexico’s failure to reform into a modern state, especially at local levels, the cartels found their opportunity. Mexico has traditionally starved its cities. They have weak taxing power. Their mayors can’t be reelected. Constant turnover breeds incompetence, improvisation, and corruption. Local cops are poorly paid, trained, and equipped. They have to ration bullets and gas and are easily given to bribery. Their morale stinks. So what should be the first line of defense against criminal gangs is instead anemic and easily compromised. Mexico has been left handicapped, and gangs that would have been stomped out locally in a more effective state have been able to grow into a powerful force that now attacks the Mexican state itself.

The first sign of trouble was Nuevo Laredo in late 2005. The Gulf and Sinaloa cartels staged street shootouts and midnight assassinations for months in this border city, which the Gulf cartel had controlled. One police chief lasted only hours from his swearing-in to his assassination. The state and municipal police took sides in the cartel fight. Newspapers had to stop reporting the news for fear of retaliation.

Enter Calderón, who took office in late 2006, determined to address the growing war among Mexico’s cartels. He broke with old half-measures of cargo takedowns that looked good but did little to damage the cartels. Calderón wanted arrests. He also began extraditing to the United States the capos and their lieutenants—more than 90 so far—who were already in custody and wanted up north.

But when Calderón looked across Mexico for allies to help him escalate the war on the narcogangs, he found few local governments and police forces that hadn’t been starved to dysfunction. So he has had to rely on the only tool up to the task: Mexico’s military. Calderón has also turned to the United States for help. The Merida Initiative, launched in April 2008, is a 10-fold increase in U.S. security assistance to a proposed $1.4 billion over several years, supplying Mexican forces with high-end equipment from helicopters to surveillance technology.

Fighting criminal gangs with a national military is an imperfect solution, but Calderón has scored some victories. He has captured or killed key gang leaders. Weapons seizures have been massive. Last November, the Mexican Army seized a house in Reynosa that contained the largest weapons cache ever found in the country, including more than 540 rifles, 500,000 rounds of ammunition, and 165 grenades.

The cartels have responded to Calderón’s war with the kind of buchon savagery that so struck me upon returning to Mexico. In addition to fighting each other, the cartels are now increasingly fighting the Mexican state as well, and the killing shows no sign of slowing. The Mexican Army is outgunned, even with U.S. support. Calderón’s purges of hundreds of public officials for corruption, cops among them, may look impressive, but they accomplish little. The problem isn’t individuals; it’s systemic. Until cities have the power and funding to provide strong and well-paid local police, Mexico’s criminal gangs will remain a national threat, not a regional nuisance.

There’s little reason to believe 2009 won’t look a lot like 2008. And there’s reason to fear it will be worse. The financial crisis is hitting Mexico hard. How long it can hang on is unclear. The momentum still favors the gangs, meaning the bloodshed will likely subside only when they tire of warring.

Americans watch this upheaval with curious detachment. One warning sign is Phoenix. This city has replaced Miami as the prime gateway for illegal drugs entering the United States. Cartel chaos in Mexico is pushing bad elements north along with the dope—enforcers without work and footloose to freelance.

Phoenix—the snowbird getaway, the land of yellow cardigans and emerald fairways—is now awash in kidnappings—366 in 2008 alone, up from 96 a decade ago. Most committing these crimes hail from Sinaloa, several hundred miles south. In one alarming incident, a gang of Mexican nationals, dressed in Phoenix police uniforms and using high-powered weapons and military tactics, stormed a drug dealer’s house in a barrage of gunfire, killing him and taking his dope.

Phoenix is hanging tough—for now. Its capable local police, so desperately lacking in Mexico, are managing to quarantine the problem. No one unconnected to smuggling has been abducted, police say, and no kidnapping victim has been lost in a case they have been asked to investigate. As a result, most Phoenix residents live blithely unaware that hundreds of people in the smuggling underworld are kidnapped in their midst every year.

Still, violence and criminality are moving north at a rapid pace, and Americans would be foolhardy to imagine capable police departments like Phoenix’s going for long without cracking under the pressure. As one Phoenix police officer told me, “Our fear is, we’re going to meet our match.”

Sam Quinones, a reporter with the Los Angeles Times, is author of two books

on Mexico. His Web site is www.samquinones.com.