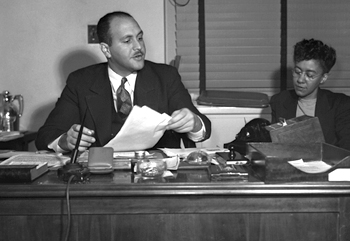

Robert Weaver, head of the Negro Employment and Training Branch, in 1942.

Robert Weaver, head of the Negro Employment and Training Branch, in 1942.WEB DuBois on the Soviet invasion of Finland: “The world is astonished, aghast, and angry! But why?...England has been seizing land all over the earth for centuries and without a shadow of rightful claim: India, South Africa, Uganda, Egypt, Nigeria, not to mention Ireland. The United States seized Mexico from a weak and helpless nation in order to bolster slavery….This is the world that has grown suddenly righteous in defense of Finland.” NAACP on 1940 elections: “What point is there in fighting and perhaps dying to save democracy if there is no democracy to save?” NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, on the buildup to war: “The hysterical cries of the preachers of democracy for Europe leave us cold. We want democracy in Alabama, Arkansas, in Mississippi and Michigan, in the District of Columbia—in the Senate of the United States.” After Pearl Harbor, it writes, “a lily-white navy cannot fight for a free world. Jim Crow strategy, no matter on how grand a scale, cannot build a free world.”

Robert Weaver, head of the Negro Employment and Training Branch, in 1942.

Robert Weaver, head of the Negro Employment and Training Branch, in 1942.

OWI pamphlet, Negroes and the War, 1942: the US Army has “two full divisions of Negro soldiers,” “Negroes serve in all branches…and there are Negro officers….Our future, like the future of all freedom lovers, depends upon the triumph of democracy.” In 1937, there are 360,000 soldiers in the military, 6500 of whom (less than 2%) are African-American. Down to 4000 (1.5%) by 1940. (Comparatively, a very good job: in 1939, average African-American yearly wage in US is $371, and $964 per capita for all. Army estimates value of service salary and benefits as $2000-4000.) In 1940, there are five African-American officers in the entire military, three of whom are chaplains. Only 17 of 1997 students in officer candidate school are African-American, July-Oct. 1941; in 1940, West Point has graduated 1 African-American cadet in 20 years; Naval Academy graduates its first in 1949. Army War College training manual, on how to deal with African-American soldiers (who are limited to a planned 6% of military): “the negro is docile, tractable, lighthearted, care free, and good natured….He is careless, shiftless, irresponsible, and secretive. He resents censure and is best handled with praise and by ridicule.” By 1942, about 10% of 4.5M enlisted soldiers are African-American, 754,000, or about 11%, in 1943. Roles not distributed equally: 40% of whites are in combat units, but only 20% of African-Americans. 35% of African-American soldiers serve in service units, compared with 14% of whites. By end of Dec. 1941, there are 5000 African-American sailors (2% of Navy), all of whom are stewards. Not until 1944 does Navy authorize African-American soldiers for duties at sea. By war’s end, 11% of white soldiers are officers, but only 1% of African-American soldiers. In a 1943 survey, ¾ of white soldiers responding think they’ve had a fair chance to help win the war, but only 1/3 of African-American troops agree.

Dorie Miller (played by Cuba Gooding in the movie Pearl Harbor), the first black man to receive the Navy Cross, for defending the USS West Virginia at Pearl Harbor.

Dorie Miller (played by Cuba Gooding in the movie Pearl Harbor), the first black man to receive the Navy Cross, for defending the USS West Virginia at Pearl Harbor.

John McCloy, asst Sec. of War, writes to William Hastie, an aide to the Secretary of War, in 1942 that “I do not think that the basic issues of this war are involved in the question of whether Colored troops serve in segregated or in mixed units, and I doubt you can convince the people of the United States that the basic issues of freedom are involved in such a question.” Chief of Staff George Marshall explains at the start of the war that it is not the Army’s job to fix America’s racial problems: “the military would be unable to solve a social problem which has perplexed the American people throughout the history of this nation. The Army cannot accomplish such a solution and should not even be charged with the undertaking.” 38 of the 50 bases housing significant numbers of black troops are in S. Donated blood, rail cars taking troops S, and air-raid shelters are all segregated. As the war ends, Army’s chief historian writes that segregation “is simply a reflection of the state of affairs well-known in civilian America today….Since the less favorable treatment characteristic of southern states is less likely to lead to violent protest from powerful white groups, the Army has tended to follow southern rather than northern practices in dealing with racial segregation.”

Howard Perry, the first black man to enlist in the Marines, 1942.

Howard Perry, the first black man to enlist in the Marines, 1942.

Opportunities: after 1942, Navy accepts black enlistment generally and as non-commissioned officers; black women are allowed to join the WAVES for the first time.

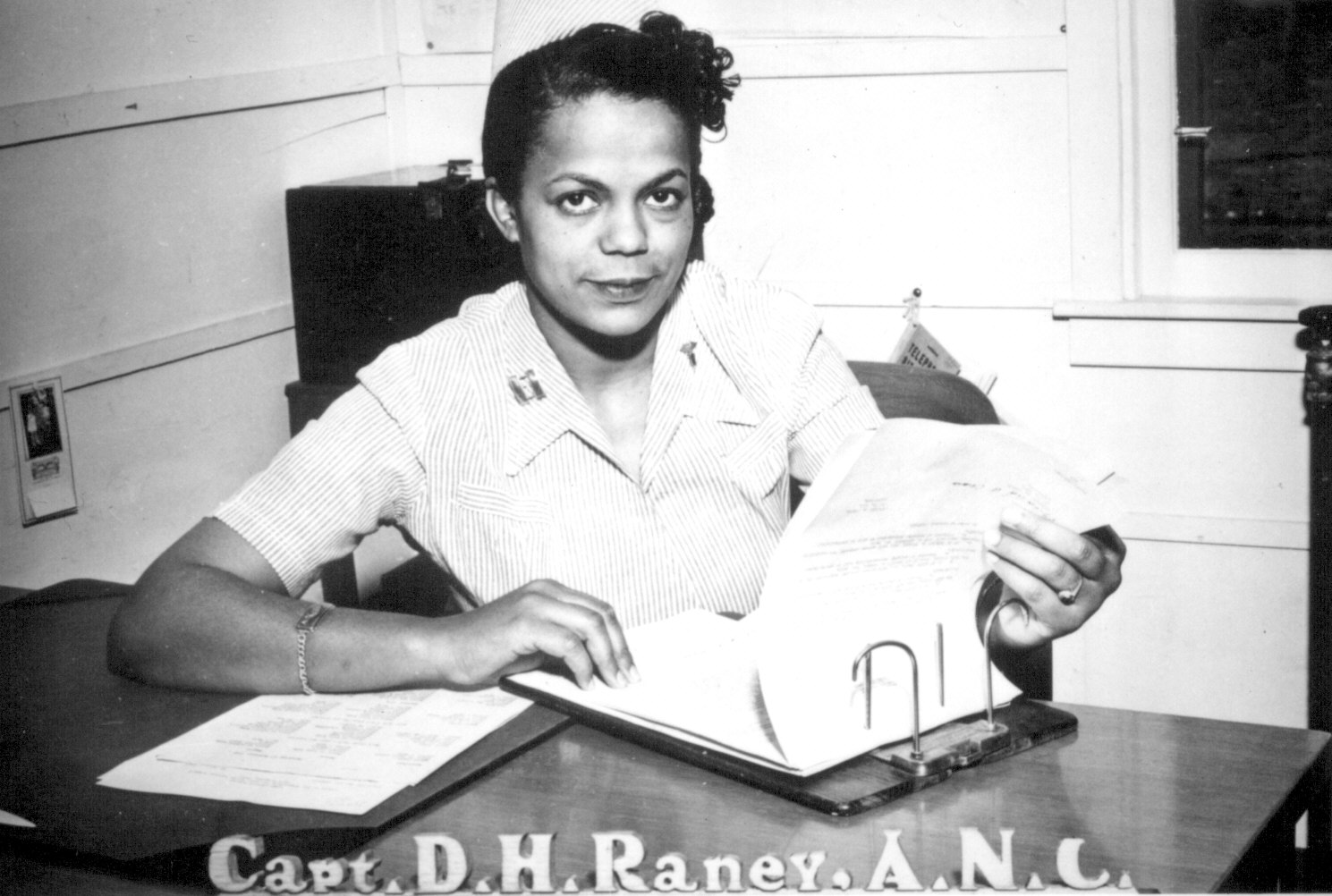

Cpt. Della Raney, the first black nurse to serve, 1945.

Cpt. Della Raney, the first black nurse to serve, 1945.

Marines, entirely segregated before this, accept black enlistment, though only in segregated units as laborers and ammo handlers. Black officers are commissioned in all branches except Air Corps, though they never command white troops. Chief of staff George Marshall pushes for and defends significant increase in numbers. In 1943, McCloy’s committee impels Marshall to instruct “under no circumstances can there be a command attitude which makes allowances for improper conduct of either white or negro soldiers.” Also orders desegregation of on-base facilities (“without instructions either implicit or implied that certain ones are for the exclusive use of either white or colored personnel”) and transportation—though this does not apply to black officers, who must live with enlisted men, unlike white officers. Even so, La. Congressman A. Leonard Allen protests: “it is a slap at every white man from Dixie wearing the uniform.” Even segregated training offers opportunities in, among other things, psychology, postal work, water purification, carpentry, painting, map reproduction, drafting, accounting, physical therapy, cooking, diesel mechanics, watch repair, navigation. “Practice aside, the dominant articulated goals of the armed services and their war aim were universal in character….Participation in this institution wrenched blacks out of a society of fixed and limited places into a world with a degree of mobility.”