Cold-War erotics were expressed in a host of areas. We see this in the opening scene of Dr. Strangelove, which depicts a plane refueling as a sex scene. The film also draws links between sexual hysteria and anti-Communism: characters with names like “Jack D. Ripper” and “Buck Turgidson,” suggesting the sexual frustration that nuclear war will alleviate; some characters fear that Communists are stealing our “precious bodily fluids,” which resonates with actual rumors that fluoridation was a Communist plot. See also The Manchurian Candidate, which is both a parody and expression of Cold-War sexual hysteria.

First, some data.

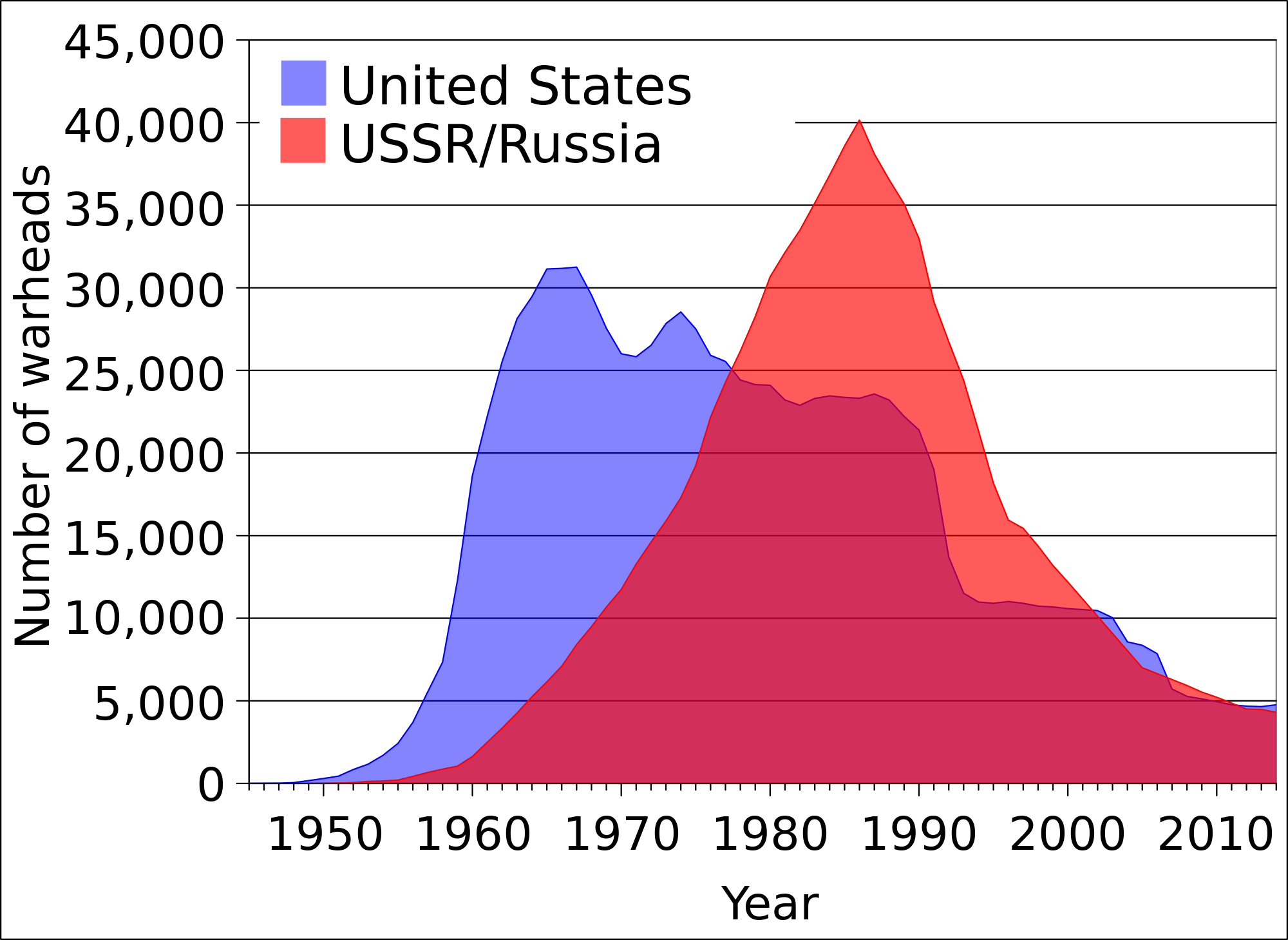

According to a 1998 Brookings Institution study, the US spent nearly 8 trillion dollars in the last half of the 20th century on nuclear weapons, about 1/3 of total US military spending on the Cold War. The nuke budget was more than the US spent in the same period on Medicare, education, social services, disaster relief, scientific research (non-nuclear), environmental protection, food safety inspections, highway maintenance, police, prosecutors, judges, and prisons. Combined. The only programs that got more were Social Security and non-nuke defense spending. It's worth noting that the US peak in actual warheads came in the early 1960s; Dr. Strangelove came out in 1964. How many missiles would you need to render the earth uninhabitable? Scientists estimated 10-100 hydrogen bombs would do the job. Both countries built way more than that.

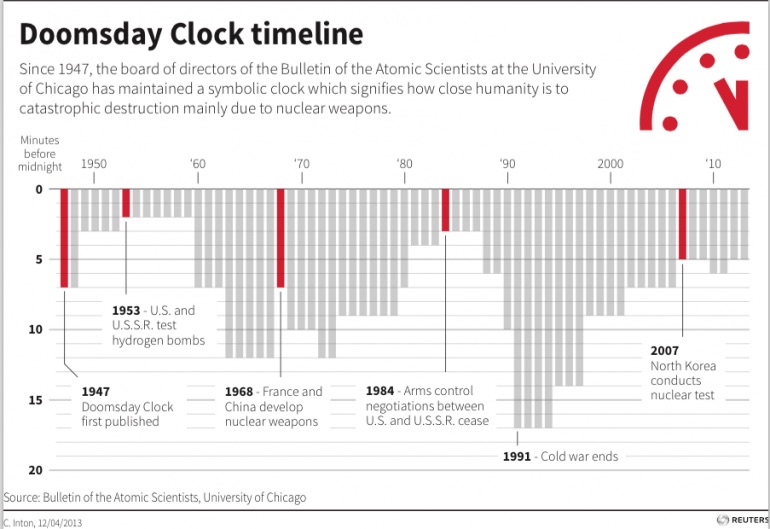

It's also interesting to note that, according to the Bureau of Atomic Scientists' Doomsday Clock, the world was actually moving away from midnight as the 60s continued:

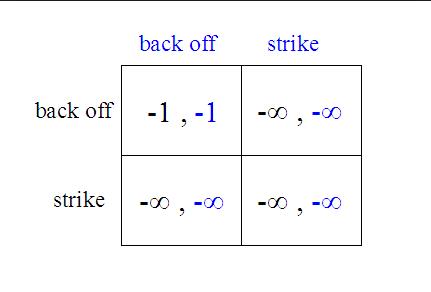

People at the time generally did not know this. In 1960, scientist CP Snow estimated that there was a mathematical certainty of nuclear war over the next 10 years. Thermonuclear war, defense theorist Herman Kahn said, was the only “acceptable” model. They literally did the math, using game theory:

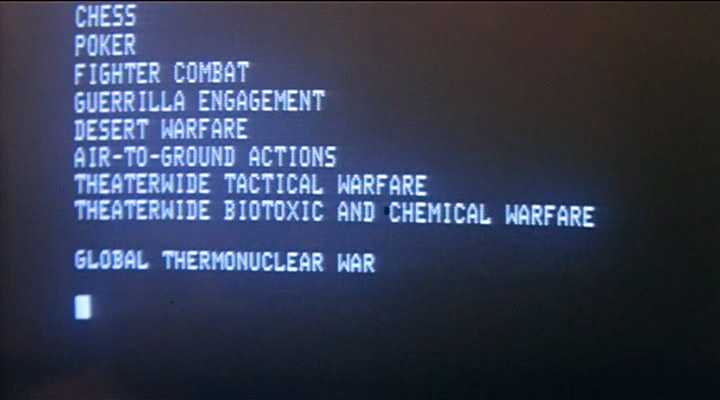

This whole defense/destruction game logic, or madness, is famously the basis for the 1983 technothriller WarGames, which is still pretty good:

The point being that both professionals and everyday people spent lots and lots of time contemplating the possible destruction of the world. This is kind of a disturbing job. (For more on this, check out this article about how people today try to make sure that nuclear scientists enjoy their work, but not, you know, too much.) In some ways, fact was stranger than fiction: the actual Dr. Strangelove (whom you'll meet in the movie) was based on both former Nazi scientist Werner von Braun, who helped the US get to the moon, and Herman Kahn, whose most famous works of what you could call “nuke porn” are On Escalation, with a 44-stage escalation ladder that included such stages as hardening of position, super-ready status, provocative counter-measures, and spasm war (think of this when you watch the refueling scene), and On Thermonuclear War, which outlines worldwide nuclear wars III-VIII.

Some US military leaders seemed waaay too eager to think about the allegedly unthinkable: the head of Strategic Air Command, General Tommy Powers, was famous for laughing off the effects of nuclear radiation on genetic mutations with the quip: "Nobody has yet proved to me two heads aren't better than one." General Powers had little time for the civilian nuclear theorists who talked of counter-force strategies, deliberately avoiding Soviet cities and attacking only their missile bases. "Restraint? Why are you so concerned with saving their lives? The whole idea is to kill the bastards," he shouted at the Rand Corporation's William Kaufmann during one briefing. "At the end of the war, if there are two Americans and one Russian, we win."

Kaufmann retorted: "Then you had better make sure that they are a man and a woman."

The US strategy, known as SIOP (Single Integrated Operational Plan), made this more likely, as it had only one response to any attack: full-scale nuclear war. There were no plans for what would happen after tens of millions of people died. "The single most absurd and irresponsible document I had ever reviewed in my life," according to General George Butler, former head of Strategic Air Command. "We escaped the Cold War without a nuclear holocaust by some combination of skill, luck, and divine intervention, and I suspect the latter in greatest proportion."

Also, at one point nuclear planners considered nuking the moon. Just to show they could.It was clear that large parts of America would not escape unscathed during a nuclear war, and in fact already had not escaped unscathed:

So upcoming wars (recall that Kahn got up to World War 8) might require the evacuation of the US “two or three times every decade.” Nuclear fallout and genetic damage were not problems in this way of thinking, b/c 4% of kids are born defective anyway; loss of 1/2 of the US population is acceptable, Kahn says: “even though the amount of human tragedy would be greatly increased in the postwar world, the increase would not preclude normal and happy lives for the majority of survivors and their descendants.”

Excerpts from the Defense Department's Emergency Plans Book, which was declassified by mistake in 1998. It was published as The Doomsday Scenario by MBI Publishing (in China, of all places). A historian, L. Douglas Keeney, discovered the plans in the National Archives and annotated the unsugarcoated text (in boldface), which resonates in the contingency strategies drawn up in Washington after Sept. 11 for preserving government operations and mounting nuclear retaliation.

The surface bursts have resulted in widespread radioactive fallout of such intensity that over substantial parts of the United States the taking of shelter for considerable periods of time is the only means of survival. . . . The general level of casualties throughout the United States is extremely serious. In many localities it is catastrophic. The population of the United States in 1958 was 140 million. Almost one in five will die.

Post-Attack Analysis: With human casualties exceeding material losses, ultimate recuperative potential to meet the requirements of the surviving population is high, providing this population can be adequately motivated. In spite of the magnitude of the catastrophe that has struck the nation and the possibility of additional but lighter attacks, more than 100 million people and tremendous material resources remain. . . . The attack has caused an almost complete paralysis in the functioning of the economic system in all of its aspects. . . . During the survival period the economy is operating in a highly disorganized manner. The utilized labor force is engaged in large numbers in disposing of the dead, taking care of surviving injured, decontaminating and cleaning up bombed areas, returning public works and utilities to operation, and other activities related to the direct and immediate effects of the attacks. . . . There are few workers left to produce goods. . . . Government control is seriously jeopardized and central federal direction is virtually nonexistent. Many of the highest government officials are casualties although the presidential office is functioning. Washington was so severely damaged that no operations there are possible. . . . In many areas, including several of the largest cities, where surviving injured outnumber the surviving uninjured active adults, the social fabric has ceased to exist in the pre-attack pattern. . . .

Here we see that even in 1958, the government actually agreed [that] shelters would be inadequate. Many would be destroyed. Most were too far away to be useful; a large number for whom the shelters were intended would die before they reached them. Those who did get in would be so badly contaminated that they would soon succumb to radiation sickness and die.

From a pre-attack total of 1.6 million hospital beds, approximately 100,000 are available for use. . . . The medical care requirements are overwhelming. In addition to 25 million dead or dying, there are 25 million surviving casualties who require emergency medical care. . . . Of the 25 million radiation casualties, 12.5 million have received lethal dosages and have died or will die regardless of treatment. . . . Inadequate provision for laboratory diagnostic aids has hampered the more accurate determination of degrees of radiation injury. Unless such determinations are made, many lives may be lost because treatment is being given to hopeless cases. . . . The housing situation is critical. . . . In only very isolated situations is the housing inventory adequate to rehouse survivors from attacked areas.

Does the author contradict an earlier assumption and now say that civilian populations were targeted? Probably not. But collateral damage in nuclear war would be unavoidable and extensive.

Blast damage has not only completely eliminated major water and sewer networks, but has at the same time dangerously impaired the function of water and sewer facilities in peripheral areas otherwise unaffected by blast and fire damage. . . . The monetary and credit systems have collapsed in damaged areas and are under severe pressure in those areas overrun with refugees. . . . Bartering, unorganized confiscation and looting are in evidence. . . . Severe disruption to transportation service exists in all attacked and contaminated areas. . . . Yes, production will be curtailed or blocked due to damage, manpower losses and radiation. But the ''X'' factor is the will of American to get back on its feet. . . . Therein lies the great strength of America: the refusal to backslide into the abyss.

_________________________________________________

You might think that this all would create mass hysteria.

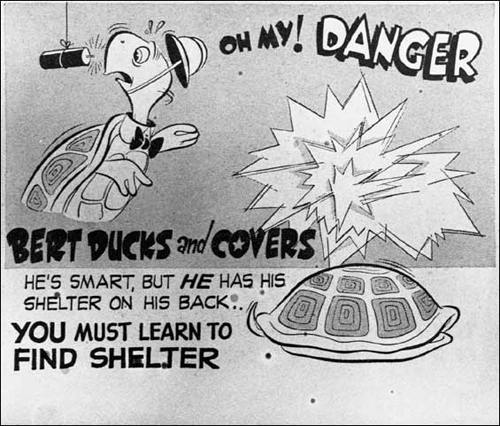

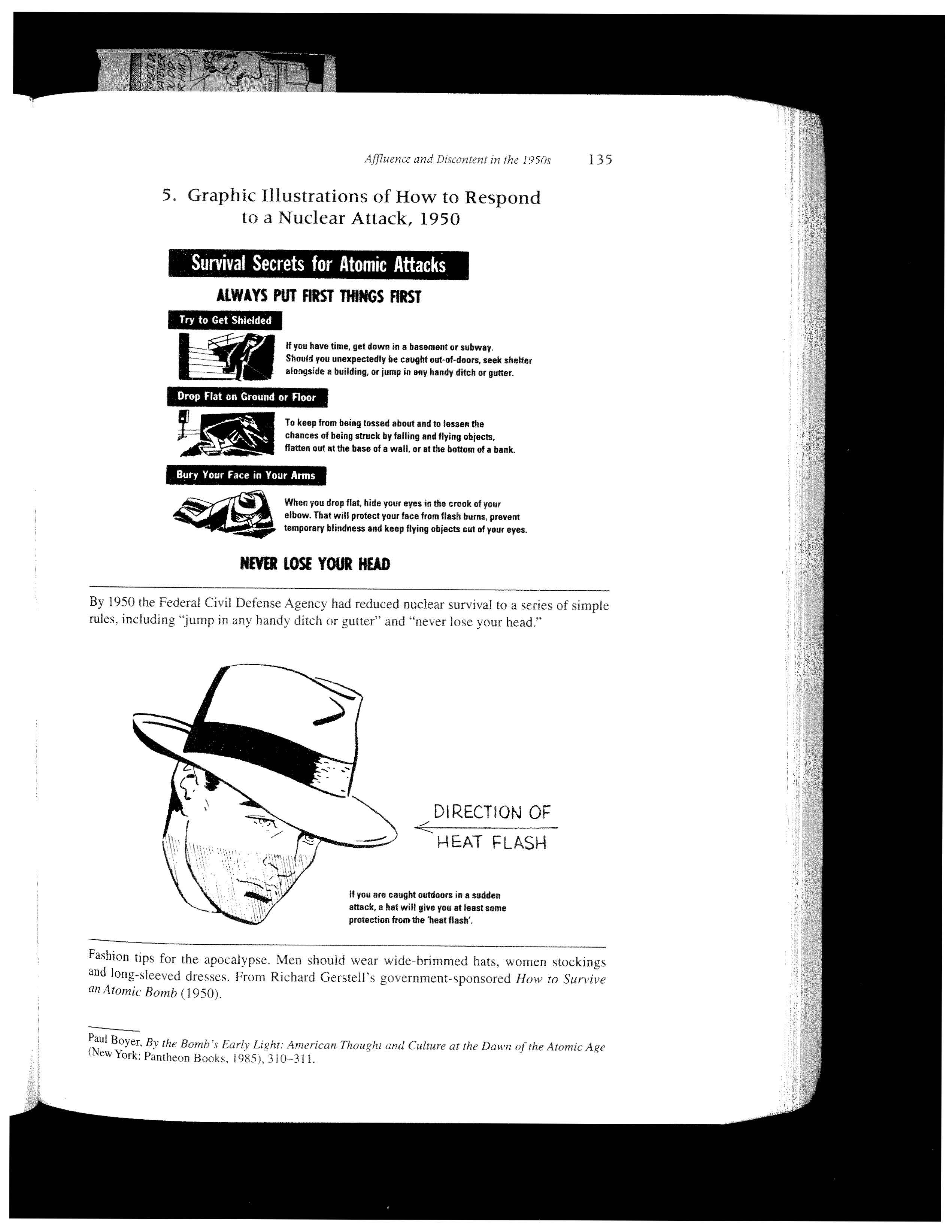

You would be wrong. Both nuclear theorists and mass-culture outlets like Life magazine spent an inordinate amount of time reassuring themselves that everything would be OK. There were the famous "duck and cover" drills telling you that hiding under a desk would save you from a bomb blast.

If you did not happen to have a desk handy, you could just use a newspaper.

But you shouldn't worry. Once you got that newspaper off your head, life would resume more or less as normal afterward. In the 50s, numerous photo spreads in Life magazine explained how to enjoy life in a shelter after such a war; one spread featured the family’s teenage daughter calling up a boy, presumably in his family’s shelter, to arrange a date for several thousand years in the future.

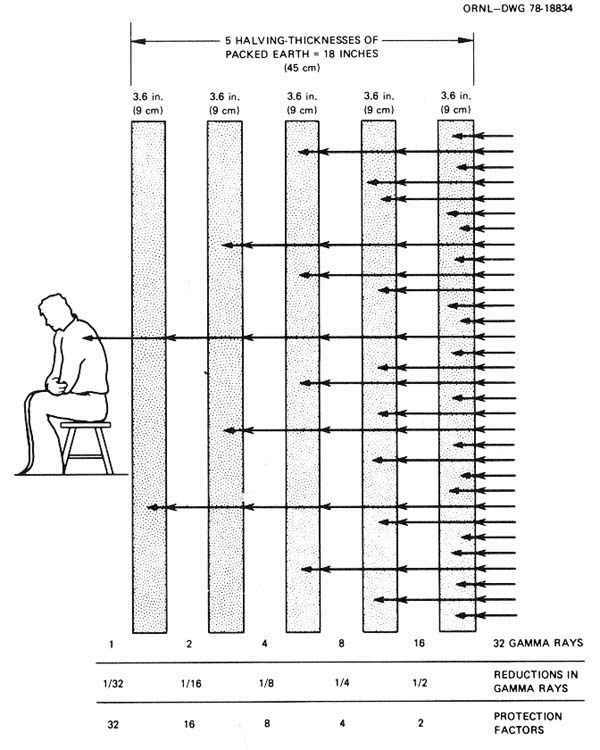

Life ran the cover story above explaining that 97 of every 100 people could be saved from an atomic blast; US News ran one called “If Bombs Do Fall,” explaining that the government had already stored enough $1 bills in strongboxes to last 8 months, and that it had worked out a way for you to write checks on your bank account even when there were no banks. The world might end, but the American way of life would go on. As you can see from this picture, not that many gamma rays would hit you if your shelter was thick enough.

So one aspect of the erotic Cold War involves adoring contemplation of the unthinkable.