Chinese transformed 'Gold Mountain'

Few struck it rich, but their work left an indelible mark

By Stephen Magagnini

Bee Staff Writer

Published Jan. 18, 1998

When news of the Gold Rush reached Canton in 1848, thousands of young Chinese mortgaged their futures and boarded boats to "Gum Shan," or "Gold Mountain," as California was known.

It was a dangerous gamble, but they had little to lose: Canton (Kwangtung) province was torn by civil war, floods, droughts, typhoons and other disasters.

By 1852, 25,000 Chinese had reached Gold Mountain. The 1852 census showed 804 Chinese males and 10 females in Sacramento.

Most had to work off the cost of their passage (between $30 and $125), and few struck it rich in the gold fields. But they would transform Gold Mountain, and America.

From the time they landed, they patiently worked long hours for low pay, quickly earning the resentment of their white competitors. In 1849, white miners drove off a team of 60 Chinese miners working for a British company at Chinese Camp in Tuolumne County.

By 1852, white miners had driven hundreds of Chinese from Columbia, Yuba City, Horseshoe Bar, Mormon Bar and other diggings. In 1856, Chinese at Mokelumne Hill in Calaveras County paid $70,000 for mining rights and "protection." In 1862, an "anti-coolie" club formed in San Francisco.

According to Hutching's Illustrated California magazine, "With the exception of leading Chinese merchants we have had the opportunity to observe only the most unfavorable specimens of this race ... throngs of coolies and degraded women." […]

Like other non-whites, Chinese could not testify against whites in court, and many were the victims of racist savagery. In Nevada City, a Chinese miner was hanged for stealing a mule -- only to have the mule's supposed owner show up and say his mule was a "jack," not the "jenny" owned by the Chinese miner.

Some Chinese, infected with gold fever, "chased gold all the way to Vancouver, Idaho and Alaska," said historian Sylvia Sun Minnick.

Despite the virulent racism they faced, many Chinese stuck it out as cooks, cigar makers, restaurateurs, vegetable farmers and merchants. The first Chinese laundry opened in San Francisco, or "Dai Fow" (Big City) in 1851; a thousand more followed.

Hundreds of Chinese lived in wood and canvas buildings in Sacramento or "Yee Fow" (second city).

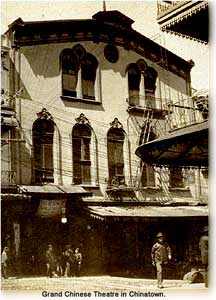

In 1854, the First Chinese Baptist Church and the Chinese Benevolent Association opened here, and they operate to this day. In 1856, the first Chinese-language daily in America, the Chinese News, rolled off the presses. The Canton Chinese Theater featured puppet shows and roving minstrels and in 1855 presented Chinese operas for an all-white audience.

Grand Chinese theatre, Jackson St.

Gambling halls, temples, fortune tellers and laundries also abounded in Sacramento's "Chinadom."

Though frequently crippled by floods or fire, it was quickly rebuilt. Minnick said, "The resilient nature of Chinese businessmen... (is) best tested after natural disasters." Four months after the July 1854 fire, five markets, one general store, a bar, a boardinghouse and three gambling houses received new business licenses.

In 1863, California's 25,000 Chinese miners enjoyed their best year, pulling gold out El Dorado, Placer, Amador, Calaveras, Butte and Trinity counties. But by 1868, nearly all had left the mines. Some joined the new wave of Chinese immigrants who came to build the western leg of the transcontinental railroad, completed in 1869.

They were hired by Charles Crocker, who figured if their ancestors could build the Great Wall over mountains and tundra, they could lay track over the Sierra Nevada.

Chinese later played a huge role in California's agricultural development, building Delta levees based on the Pearl River Delta in Kwangtung province, planting orchards and raising potatoes, onions and asparagus.