1828 election:

Elections back then were hotly contested,

with the facts often slanted. Broadsides (early, crude posters) were circulated

both for and against Jackson.

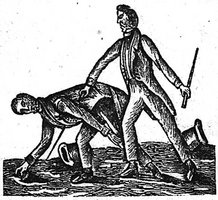

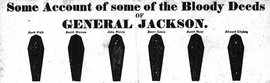

John Binns, editor of the Philadelphia Democratic Press, printed an

anti-Jackson broadside that depicted six coffins containing militiamen, who, “an

eye witness” alleged, had been executed wrongfully, on General Jackson’s

orders during the War of 1812. In addition, it showed another dozen coffins,

representing regular soldiers and “Indians” who were put to death

under Jackson’s command. There was also a drawing of Jackson on a

city street, running his sword through a man’s back.

Editorial cartoon referring to Jackson's execution of soldiers who sympathized with the Seminole Indians during the war of 1812. It declares "Jackson is to be president and you will be HANGED."

John Quincy Adams called the Jackson men “skunks of party slander,” but they attacked him very effectively. After this "Coffin Handbill" first appeared, Jackson had his “Nashville Committee” of supporters answer the charges, stating that those executed had been guilty of mutiny, theft, arson, and desertion. Just as they do today, campaigns needed to have response teams in place to counter the political ads of the opposition.

From Michael F. Holt's book The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party:

[In the presidential campaign of 1828, Jackson supporters] disseminated propaganda

. . . reminding voters that [Jackson] had been the victim of a corrupt and

cynical bargain, pillorying the supposed misdeeds of the Adams administration,

and lacerating the president himself as an effete intellectual snob who spoke

Latin and quoted Voltaire; as a papist or an antipapist, depending upon the

audience; and even as a former pimp for the czar of Russia [Adams was born

in 1767 and served as an assistant to Francis Dana in St. Petersburg in 1781-82

-- in other words, at age fourteen]. Isaac Hill, editor of the New Hampshire Patriot, called him "the panderer of an Autocrat" who had sent the Adams children's nanny to parade before the Czar, who fortunately found her "less voluptuous than his gorged appetite could relish." Jackson allies nicknamed Adams "the

Pimp." Jackson's forces also alleged that Louisa Adams had been an illegitimate

child

who had indulged in pre-marital sex with John Quincy Adams.

“His habits and principles are not congenial with…the notions of a democratic people,” one Jackson supporter wrote. Others whispered about Adams’s “foreign wife”--Louisa was English. When the President bought a billiard table and set of ivory chessmen for the White House he was accused of purchasing a “gaming table and gambling furniture.” He also purchased a backgammon board, dice, chess and soda water, spending, according to one anonymous letter written by Senator Thomas Hart Benton, $25,000 of the people's money on luxuries. Which was not true--Adams had paid for the table himself. Adams was called a monarchist and anti-religious, because he traveled on the Sabbath. And he was of course smeared by his association and friendship with Secretary of State Henry Clay, who supposedly owed his position to the “corrupt bargain.” (Clay was not a statesman, snarled The New Hampshire Patriot, but “a shyster, pettifogging in a bastard suit before a country squire [Adams].”)

Adams supporters got organized and returned fire with a vengeance. Jackson, they said, had aided Aaron Burr when the latter conspired against the union in 1806, and had invaded Florida and nearly started an international incident. He had the personality of a dictator. Not only that, he couldn’t spell (supposedly, he spelled “Europe” “Urope”). The Whigs also published an extremely nasty little pamphlet called Reminiscences; or, an Extract from the Catalogue of General Jackson’s Youthful Indiscretions between the Age of Twenty-three and Sixty. It enumerated all fourteen of Jackson’s purported fights, duels, brawls, and shoot-outs and claimed that he had "killed, slashed, and clawed various American citizens." It also said he was an adulterer, a gambler, a cockfighter, a slave trader, a drunkard, a thief and a liar, and that his "intemperate life and character" rendered him "unfit for the highest civil appointment." Cincinnati editor Charles Hammond, publisher of a pamphlet called "Truth's Advocate and Monthly Anti-Jackson Expositor," announced that Jackson's mother was "a COMMON PROSTITUTE brought to this country by British soldiers," and also that "she afterward married a MULATTO MAN with whom she had several children, of which General JACKSON IS ONE!"

Also, they said his wife was fat. Rachel Jackson (a "coarse-looking stout little old woman whom you might easily mistake for his washer-woman if it were not for the marked attention he pays her," according to the daughter of one of his officers) had married Andrew but was unaware that her first husband had not finalized their divorce. "Ought a convicted adulteress and her paramour husband to be placed in the highest offices of the free and Christian land?" wrote Adams supporters. They waved banners outside a Tennessee hotel in which Jackson was staying that said "the ABC of Democracy. The Adulteress, the Bully, and the Cuckold." The story was brought up on the campaign trail, and the legend is that, shopping for a gown for the inauguration in Nashville, Rachel Jackson found a copy of Hammond's "Truth's Advocate," wept hysterically, and apparently had two heart attacks by the end of the year, then died three days before Christmas. ("She was indeed a fortunate woman," wrote the New York American, since she therefore escaped all the attacks she would have suffered in the White House.) Jackson blamed Adams for his wife's death ("I can and do forgive my enemies," he wrote, "but those vile wretches who slandered her must look to God for mercy"); Adams left Washington before the new president's inaugural.

Jackson did not like Adams' attacks. He wrote to a friend that "the whole object of the coalition is to calumniate me, cart-loads of coffin handbills, forgeries, and pamphlets of the most base calumnies are circulated by the franking privilege of Members of Congress. Mrs. Jackson is not spared, and pious Mother, nearly fifty years in her tomb, and who, from her cradle to her death, had not a speck upon her character, has been dragged forth...and held to public scorn as a prostitute who intermarried with a Negro, and [it is alleged that] my eldest brother [was] sold as a slave in California....I am branded with every crime."

Adams, saddened by losing the election, spends a year or so writing an epic poem that obliquely mourns his loss.from the 1836 election:

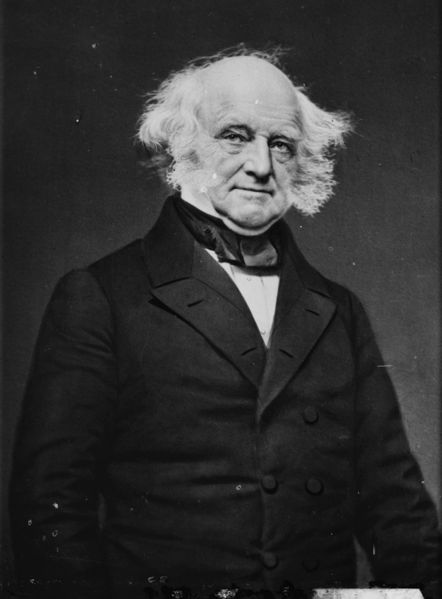

William Henry Harrison, one of 4 Whig candidates, travels to Va. not to campaign, which would be unseemly, but to “counteract the opinion, which has been industriously circulated, that I was an old broken down feeble man.” Davy Crockett, the Whigs' own Tennessee leatherstocking, wrote (or had ghost-written) a campaign biography depicting "little Van" as a fop. Van Buren, it said, turned up his nose at the common people he presumed to lead, rode about in a carriage with servants in uniform ("I think they call it livery"), dressed like a lord, and "is laced up in corsets, such as women in town wear. . . . It would be difficult to say, from his personal appearance, whether he was a man or woman, but for his large red and gray whiskers."

from Walter A. McDougall, Throes of Democracy: The American Civil War Era 1829-1877, 91-92.

from 1840:

One of the Whigs' principal "attack ads" was a pamphlet that reprinted excerpts from a 3-day-long speech by Charles Ogle, a Whig congressman from Pennsylvania, entitled "The Regal Splendor of the Presidential Palace." Much of the pamphlet was devoted to the opulent splendor in which Van Buren allegedly lived while the nation suffered through a major depression. But it also included lurid suggestions of sexual depravity. As Sean Wilentz relates, Ogle asserted that

the degenerate widower Van Buren had instructed groundskeepers to build for him, in back of the Executive Mansion, a large mound in the shape of a female breast (specifically, a Pennsylvania congressman accused him of landscaping the White House grounds into hills resembling "an Amazon's bosom"), topped by a carefully landscaped nipple. Van Buren . . . was a depraved executive autocrat who oppressed the people by day and who, by night, violated the sanctity of the people's house with extravagant debaucheries -- joined, some whispered, by the disgusting Vice President Johnson and his Negro harem.

In order to fully appreciate the closing reference, you need some background

on Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson. He was a Kentucky slaveholder who made no effort to disguise his liaisons

with black women. Again, Sean Wilentz tells the story succinctly:

Johnson had two daughters, Imogene and Adeline, by his housekeeper, a biracial ex-slave named Julia Chinn. After Chinn died in 1833, Johnson took up with another woman of partial African descent, and in Washington he accompanied his out-of-wedlock daughters (whom he had provided with excellent private educations) to public functions and festivities, sometimes in the company of their respective white husbands.

After Johnson's election in 1836, there was talk that he had entered into yet another illicit liaison with a mixed-race woman, aged eighteen or nineteen, who was the sister of one of his previous consorts. (After a trip to Kentucky, Amos Kendall informed friends that Johnson was devoting "too much of his time to a young Delilah of about the complexion of Shakespears swarthy Othello." Here's a racist cartoon attacking Johnson and his family.) Johnson was so controversial that 23 "faithless electors" (members of the electoral college who refused to vote for their party's choice) deserted the Democrats in 1836. This period represents by far the largest number of such electors in US history: 7 in 1828 and 32 in 1832.

In 1840, Democrats called Harrison “a living mass of ruined matter” and a “superannuated and pitiable dotard" and WHH had a doctor attest to his “vivacity and almost youthfulness of feelings…his intellect is unimpaired.” Dems: “We know not whether most to scorn his imbecility, to hate his principles or wonder at his impudent effrontery." Lincoln endorses WHH, sort of: "When an individual’s hairs have grown grey and his eyes dim in the service of his country, it seems to us, if his countrymen are wise, and polite, they will reward him…”

The Hard Cider image comes from the Ohio state Whig celebration of WHH’s nomination, according to a friendly newsman: “yonder comes a real, bona fide log cabin! See the raccoon skins hanging out upon its sides. Upon the door is written with charcoal, in awkward characters, ‘Hard Cider.’ It is filled with men in hunting shirts, eating corn-bread…” Whigs had a Log Cabin Songbook, Log Cabin Anecdotes, dances called Tippecanoe Quick-Step, which you could dance at a Harrison Hoe-Down, Tippecanoe shaving soap, Tippecanoe Tobacco, many versions of the Harrison-and-Tyler Necktie; they also published numerous Log Cabin periodicals and almanacs, Hard Cider Press, and one from Cleveland called Hard Cider for Log Cabins. They even passed around stories about young women who would not marry any young man who failed to support the campaign.

After being elected, WHH walked by himself around DC, shaking hands with people, dropping in unexpectedly on the Senate, even going to DC’s only bookstore to buy a bible for the White House, which did not have its own copy. He gets sick soon after his inaugural, then dies, making him the shortest-serving president of all time. It has been typically ascribed to pneumonia but was probably enteric fever, which he might have gotten from the open-sewage marsh near the White House.