Ellen DuBois, "Reconstruction and the Battle for Women Suffrage," HistoryNow

The Fifteenth Amendment, passed by Congress in 1869 and ratified a year later, explicitly forbade the states to deny the right to vote to anyone on the basis of “race, color or previous condition of servitude” and authorized Congress to pass any necessary enforcement legislation. The wording, it should be noted, did not transfer the right to determine the electorate to the federal government, but only specified particular kinds of state disfranchisements—and “sex” was not one of them—as unconstitutional.

At this point, the delicate balance between the political agendas of the causes of black freedom and women’s rights became undone. The two movements came into open antagonism, and the women’s rights movement itself split over the next steps to take to secure women the right to vote. Defenders of women’s rights found themselves in an extremely difficult political quandary. Would they have to oppose an advance in the rights of the ex-slaves in order to argue for those of free women? At a May 1869 meeting of the American Equal Rights Association, a group that had been organized three years earlier by women’s rights advocates to link black and woman suffrage, Elizabeth Cady Stanton  gave vent to her frustration, her sense of betrayal by longstanding male allies, and her underlying sense that “educated” women like herself were more worthy of enfranchisement than men just emerged from slavery. She had said the following on Jan. 19, 1869 to a women's suffrage convention:

gave vent to her frustration, her sense of betrayal by longstanding male allies, and her underlying sense that “educated” women like herself were more worthy of enfranchisement than men just emerged from slavery. She had said the following on Jan. 19, 1869 to a women's suffrage convention:

I urge a Sixteenth Amendment because, when "manhood suffrage" is established from Maine to California, woman has reached the lowest depths of political degradation. So long as there is a disfranchised class in this country, and that class its women, a man's government is worse than a white man's government with suffrage limited by property and educational qualifications, because in proportion as you multiply the rulers, the condition of the politically ostracised is more hopeless and degraded....If American women find it hard to bear the oppressions of their own Saxon fathers, the best orders of manhood, what may they not be called to endure when all the lower orders of foreigners now crowding our shores legislate for them and their daughters? Think of Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Yung Tung, who do not know the difference between a monarchy and a republic, who can not read the Declaration of Independence or Webster's spelling-book, making laws for Lucretia Mott, Ernestine L. Rose, and Anna E. Dickinson.

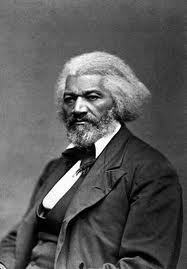

She and Frederick Douglass

had a painful and famous public exchange about the relative importance of black and woman suffrage, in which Douglass invoked images of ex-slaves “hung from lampposts” in the South by white supremacist vigilantes:

and Stanton retaliated by asking whether he thought that the black race was made up only and entirely of men and whether only men faced such dangers. "Yes," Douglass replied, "that is [also] true of the black woman, but not because she is a woman but because she is black."

By the end of the meeting, Stanton and Susan B. Anthony had led a walkout of a portion of the women at the meeting to form a new organization to focus on women’s suffrage, which they named the National Woman Suffrage Association.

A second group, under the leadership of Massachusetts women Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe, formed a rival organization, known as the American Woman Suffrage Association. This wing counted on longstanding connections with abolitionism and the leadership of the Republican Party to get women’s suffrage enacted once black male suffrage had been fully inscribed in the Constitution. Over the next few years, both the American and the National Woman Suffrage Associations spread their influence to the Midwest and the Pacific Coast. The National Woman Suffrage Association linked political rights to other causes, including inflammatory ones like free love, while the American Woman Suffrage Association kept the issue clear of “side issues.” For the next few years, the two organizations pursued different strategies to secure for votes for women. Starting with an 1874 campaign in Michigan, the American Woman Suffrage Association pressed for changes in state constitutions. Because these campaigns involved winning over a majority of (male) voters, they were extremely difficult to carry out, and it was not until 1893 that Colorado became the first state to enfranchise women.

Meanwhile, the National Woman Suffrage Association refused to give up on the national Constitution. Doubtful that any additional federal amendments would be passed, the group sought a way to base women’s suffrage in the Constitution’s existing provisions. Its “New Departure” campaign contended that the Fourteenth Amendment’s assertion that all native-born or naturalized “persons” were national citizens surely included the right of suffrage among its “privileges and immunities,” and that, as persons, women were thus enfranchised. In 1871, the notorious female radical Victoria Woodhull  made this argument before the House Judiciary Committee. The next year, hundreds of suffragists around the country went to the polls on election day, repeating the arguments of the New Departure, and pressing to get their votes accepted.

made this argument before the House Judiciary Committee. The next year, hundreds of suffragists around the country went to the polls on election day, repeating the arguments of the New Departure, and pressing to get their votes accepted.

Among those who succeeded—at least temporarily—was Susan B. Anthony, who cast her ballot for Ulysses S. Grant. Three weeks after the election, Anthony was arrested on federal charges of “illegal voting” and in 1873 was found guilty by an all-male jury. Anthony was prevented by the judge from appealing her case but another “voting woman,” Virginia Minor, succeeded in making the New Departure argument before the US Supreme Court in 1874. In a landmark voting and women’s-rights decision, the Court ruled that although women were indeed persons, and hence citizens, the case failed because suffrage was not included in the rights guaranteed by that status. The 1875Minor v. Happersett ruling coincided with other decisions that allowed states to infringe on the voting rights of the southern freedmen, culminating over the next two decades in their near-total disfranchisement.

gave vent to her frustration, her sense of betrayal by longstanding male allies, and her underlying sense that “educated” women like herself were more worthy of enfranchisement than men just emerged from slavery. She had said the following on Jan. 19, 1869 to a women's suffrage convention:

gave vent to her frustration, her sense of betrayal by longstanding male allies, and her underlying sense that “educated” women like herself were more worthy of enfranchisement than men just emerged from slavery. She had said the following on Jan. 19, 1869 to a women's suffrage convention:

made this argument before the House Judiciary Committee. The next year, hundreds of suffragists around the country went to the polls on election day, repeating the arguments of the New Departure, and pressing to get their votes accepted.

made this argument before the House Judiciary Committee. The next year, hundreds of suffragists around the country went to the polls on election day, repeating the arguments of the New Departure, and pressing to get their votes accepted.