May 13, 1991

Time

How The West Was Spun

By ROBERT HUGHES

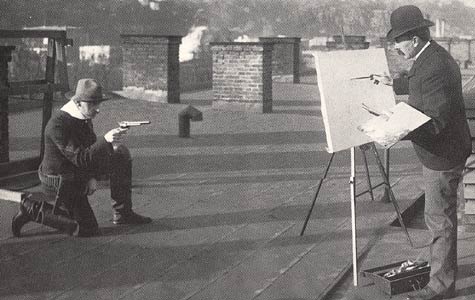

The first photograph in the catalog of "The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820-1920," the large and deeply interesting show now on view at Washington's National Museum of American Art, has to be one of the funniest ever seen in a museum. It is of Charles Schreyvogel, a turn-of-the-century Wild West illustrator, painting in the open air. His subject crouches alertly before him: a cowboy pointing a six-gun. They are on the flat roof of an apartment building in Hoboken, N.J. Such was the "authentic West" of Schreyvogel and other painters like Frederic Remington and Charles Russell, circa 1903.

It is the right emblem for this show. Religious and national myths are made, not born; their depiction in art involves much staging, construction and editing, under the eye of cultural agreement. Whatever the crucifixion of a Jew on a knoll 2,000 years ago looked like, it wasn't Tintoretto. And the American West of the 19th century was rarely what American artists set out to make it seem.

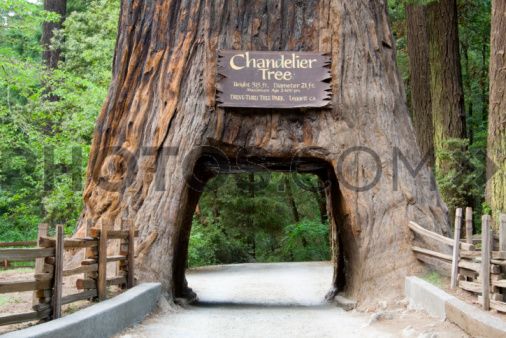

What they left, instead, is a foundation myth in paint and stone. Its main character is God, the approving father, as manifested in the landscape that he had created and that white migrants were now taking for themselves. Its human actors are frontier scouts and settlers, cavalrymen and trappers, and the American Indians -- noble at first, then seen as degenerate enemies of progress as the century went on and their resistance grew, and finally (by the 1890s) turning into doomed phantoms. Its landscapes are prodigious. Its stage material includes the Conestoga wagon, the simple cabin, the tepee, the isolated fort, the deep perspective V of the railroad -- and at the end, symbol of absolute victory over nature, the California sequoia with a road cut through its trunk.

Among the painters of this myth were George Catlin, friend of the explorer William Clark and indefatigable painter of native tribes; George Caleb Bingham, that vigorous orderer of American genre scenes; the landscapists Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran; and a host of lesser figures, who also played their part in the creation of a heroic imagery of national conquest. And here the difficulty rises, for Americans still wish to believe in the "historical" truth of their icons, which is what such pictures have become.

"The West as America" comprises hundreds of items -- paintings, sculpture, prints, photographs, caricatures -- and is an enlightening exhibition, though not a consoling one. John Wayne would have disapproved. The exhibition shows how the vast exculpatory fiction of Manifest Destiny wound its way round the facts of conquest and turned them into art. It therefore does a valuable service, even in the banal aesthetic quality of much of the work in it -- those earnest efforts of small, provincial talents whose work would not be worth studying except for the clarity with which it enshrines the obsessive themes of an expansionist America.

The American West of Hollywood was there in art, 70 years before, in most of its shades of triumphalism and moral uncertainty. It is the nature of big subjects to produce floods of bathos, as well as a few masterpieces, and to foster works of singular political equivocation.

It is fascinating to see how prototypes from older art were adapted to the artists' ends. Thus the motif of Moses leading the Exodus becomes Bingham's image of Daniel Boone escorting settlers through the Cumberland Gap toward the promised land; thus the buckskin-clad immigrant and his family are consciously meant to evoke Joseph, Mary and Jesus on the flight into Egypt. The religious imagery sometimes amounts to a suffocating pietism, but that was America too. It still is.

But when you have seen the rhetoric of Manifest Destiny in the paintings of, say, Albert Bierstadt -- the tiny wagons advancing into those golden floods of light from the westering sun, the absence of opposing Indians, the implicit approval of Jehovah himself -- you still have to decide how good they are as art. This is why the dubious orthodoxy of art-historical deconstruction is so popular. It aborts the problem by collapsing everything into ideology and fatuously claiming that the idea of "quality" is either meaningless or oppressive. It appeals to sanctimony and makes the stuff easy to teach. It lets academics feel radical. Above all, by recognizing how full of social messages bad art as well as good can be, it expands the range of available thesis subjects and thus brings relief to the eaten-out pastures of American academe.

We then come to imagine that all works of art carry sociopolitical messages the way brown bags carry sandwiches: open the flap and there they are. When one reads a cultural historian like Simon Schama reflecting on the art and society of 17th century Holland, one sees what deep access a contextual approach can give to culture. But this is a very far cry from the ritual indictments of the past on the grounds of racism, sexism, greed and so forth that increasingly substitute for thought among our academics. Lo, the Native American! See, he is depicted as dying! And note the subservient posture of the squaw! And the phallic arrow on the ground, emblem of his lost though no doubt conventionally exaggerated potency! Eeew, gross! Next slide!

Is "The West as America" free from this? By no means. Its tone is prosecutorial, and often unfairly so. The walls are laden with tendentious "educational" labels, seemingly aimed at 14-year-olds. The catalog essays are mostly better than this, but not always. Thus Julie Schimmel, writing of Charles Bird King's 1822 portrait of Omahaw and other Indian chiefs who visited Washington -- an image that could hardly be exceeded in straightforwardness and respect for the sitters -- claims that "they represent a race that could perhaps be persuaded by rational argument . . . to abandon tribal tradition." There is not a shred of evidence in the painting for this sanctimonious interpolation. Elsewhere one reads that "rectilinear frames . . . provide a dramatic demonstration of white power and control." Sure, and gilt rococo ovals would mean drag queens had taken over the Senate.

The two best catalog essays are by William H. Truettner: they set out the propagandistic themes of most Western art and are especially good on the ideology of "enlightenment" that supported and sugared the cruel facts of European conquest and expansion. Solid thought and research lie behind them, and though the conservative would complain that we know the story of Manifest Destiny's barbarous self-interest, the point is that until this show, we did not know (or certainly not in such detail) about its ramifications in painting and sculpture.

Yet even Truettner pushes too far. For instance, he sees Emanuel Leutze's The Storming of the Teocalli by Cortez and His Troops, 1848, as a celebration of Christian virtue conquering Aztec barbarism. But the image is far more melancholy and ambiguous than that: the Spanish conquistadors are presented as brutes, one flinging a baby from the temple top, another tearing loot from a corpse; and Leutze's intent to provoke pity for the Aztecs is summed up in an upside-down torch, nearly out, which lies on the steps in the foreground, an adaptation of the classic funerary image of the reversed torch of extinguished genius. Even mediocre artists like Leutze, it seems, can sometimes be a little more complex than their interpreters might wish.

ART HISTORIAN TAKES NEW LOOK AT OLD WEST

STANFORD - Their paintings of the Old West, with such evocative titles as "Old Stagecoach of the Plains" and "Fight for the Water Hole," symbolize for many Americans a bygone era.

Frederic Remington and Charles Russell are probably the most famous of America's Western artists.

Yet their works are more complex than simple illustrations of the West, says Alexander Nemerov, Stanford University art historian and author of a forthcoming book on Remington. The artists reflect issues of class, race and social Darwinism in their time, he said.

Nemerov became interested in Western artists when, as a doctoral student in art history at Yale University, he did research for a 1991 Smithsonian exhibition called "The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier" at the National Museum of American Art.

The exhibit was controversial - Daniel Boorstin, librarian of Congress emeritus, called it "perverse, historically inaccurate and destructive," and two Republican senators accused the Smithsonian of advancing a leftist political agenda.

The critics objected to the wall labels at the exhibit, with their suggestions that the paintings can be seen as more than a straightforward portrait of Western expansion. But to Nemerov, the contradictions and layers of meaning make the works of Remington and Russell more interesting.

Remington, whom Nemerov calls "the quintessential cowboy painter," was an urbane Easterner who lived in New Rochelle, N.Y. When Remington wanted to paint a buffalo, "he went to the Bronx Zoo," Nemerov said. "If he wanted his Indian model to pose, he called him on the phone and told him to come over."

In Remington's art, Nemerov believes, cowboys and Indians became a powerful metaphor for class and race issues in the industrialized, urban United States at the turn of the century.

"In other words," Nemerov said, "if you had a group of heroic white soldiers desperately trying to close the gates of a fort against an advancing racial enemy - Indians encroaching on top of the stockade - could you not relate that to contemporary images of Uncle Sam cowering before a so-called tide of immigrants?"

Remington, who traced his American roots back to 1637, viewed immigrants from central and southern Europe as, in his words, "anarchistic foreign trash" and "social scum."

"And those were two of his milder epithets," Nemerov said.

But despite his racial views, which were not unusual in their time, Remington certainly did not intend to create allegories or commentaries on immigration in his paintings, Nemerov said.

Nevertheless, "the drama of racial warfare you see over and over in these paintings relates not so much to what actually happened in the West as to a vision of the West formed in a specific political climate, namely, an urban industrial climate, wherein so-called original Americans, or English Americans, felt traumatized by this massive influx of people they would have seen as racial outsiders."

Russell, unlike Remington, spent most of his life in the West. Born in St. Louis, he moved to Montana in 1880 at the age of 16. He was a cowboy for about 12 years before becoming a full-time artist.

Although he had lived with Indians for a time, Russell's paintings continually present images of the inevitable extinction of Native Americans, Nemerov said.

Typical Russell paintings depict Indians standing on a bluff and looking out into the distance, where they see the first train, or the first steamboat, or the tracks of a covered wagon. "It hardly matters what they see, as long as it's an emblem of encroaching civilization," Nemerov said.

Russell's paintings partake of the social Darwinism of their time, Nemerov said, "in which the 'weaker' or 'more primitive' are posited as disappearing in the face of greater or better competition."

On the hills around Great Falls, Mont., Russell's home, lived Indians for whom the Montana reservation system had no room. Unlike some of his neighbors, who wanted to forcibly deport the homeless Indians across the border, Russell worked for a "more humane" means of removal, namely the establishment of another reservation, Nemerov said.

Nonetheless, he argues that Russell's paintings, which show Indians awestruck or confused in the face of technology, helped create the sentiment that the Indians were "primitive" and should therefore be removed in one way or another.

So, although Russell was hardly the bigot that Remington was, Nemerov said, his art "contributed to what it is hard not to regard as a defamation of Indian cultures."

Both Remington and Russell were nostalgic artists, Nemerov said. "Their paintings come to us from people who were profoundly, self- consciously estranged from what they thought of as a better time."

And it was not only Indians who were being pushed aside in the settlement of the West. For Remington and Russell, other Western traditions too were passing.

One of Russell's most famous paintings, "The Hold Up," depicting an actual stagecoach robbery, illustrates this change, Nemerov said.

The passengers, who are lined up, include the schoolmarm, the gambler, the miner with his pickax, the old biddy - all caricatures or stereotypes, Nemerov said. Also among the passengers are a Chinese man, rendered in caricatured fashion, and a man dressed in suit and hat, whom legends associated with the painting identify as Isaac Katz, a Jewish businessman en route from New York to Montana to open a clothing store.

In the painting, Nemerov said, the bandit represents the older way of life in the West, and the passengers represent the coming of the new.

"I think those passengers - particularly the women, the Chinese man and the Jewish businessman - all represented bad things for Russell: the coming of civilization and the replacement of an older way of life with the new," Nemerov said.