The Republican Party became

increasingly divided ideologically during the presidency of William Howard

Taft. In the congressional elections of 1910, conservative Republicans, backed

by the president, fared poorly and the GOP lost control of the House of

Representatives to the Democratic Party. However, progressive Republicans did

well in the election, and that December organized the National Progressive

Republican League to promote reform legislation. An unstated purpose of the new

group was to replace Taft as the party’s 1912 nominee with a progressive,

presumably Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin.

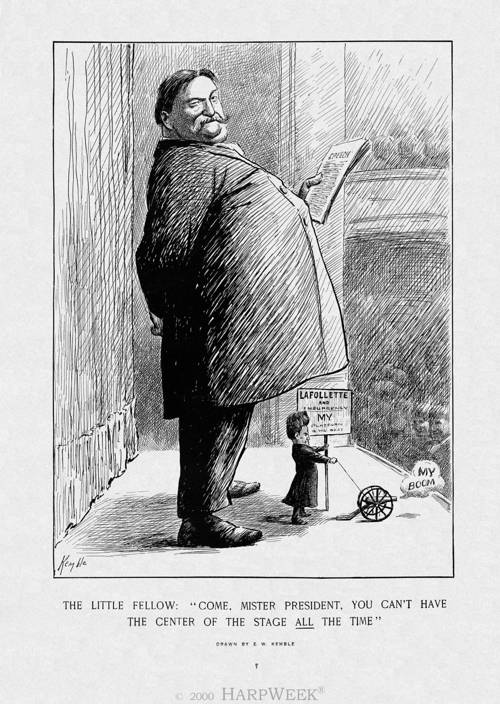

This Harper’s Weekly cartoon, published almost a year before the 1912

election, makes light of La Follette’s presidential

boom. He is portrayed as a “Little Fellow” with a toy

cannon who stands under the girth of the towering Taft, who winks confidently

at the readers.

Although he went on a speaking tour during

the primary season, after his nomination Taft abided by the tradition of

incumbent presidents not openly campaigning for reelection. His political

activities were limited to writing a few public letters on the issues.

Republicans relied heavily on advertising, and even showed a movie reel about

their nominee in 1,200 theaters. In contrast to the primaries, Taft

refused to demean the character of his rivals. Privately, though, he

disparaged the Progressive Party and Roosevelt as “a religious cult with a

fakir at the head of it.” As the post-convention campaign began, Taft

remarked to a friend, “I have no part to play but that of a conservative.”

Therefore, he defended the status quo against the policy proposals of his

opponents. He stood fast for the traditional Republican commitment to

protective tariffs, warning that Wilson and the Democrats were free traders who

threatened the nation’s economic prosperity. He considered the

Progressive Party agenda as even more ominous. Referring to it in his

acceptance speech, Taft spoke of radical ideas that would undermine “our

present constitutional form of representative government and our independent

judiciary.”

Most of the professional politicians stayed loyal to

Taft when Roosevelt and the Progressives split from the Republican Party.

Nevertheless, the president’s campaign organization suffered from a lack of

money. The GOP treasury collected about $1 million dollars ($18.3 million

in 2002 dollars), only about half the usual total, since the major donors were

reluctant to contribute to what they considered a losing cause. Even the

candidate had privately concluded that he would not be reelected.

Although reluctant to campaign actively,

the austere

Wilson U.S. Wilson America

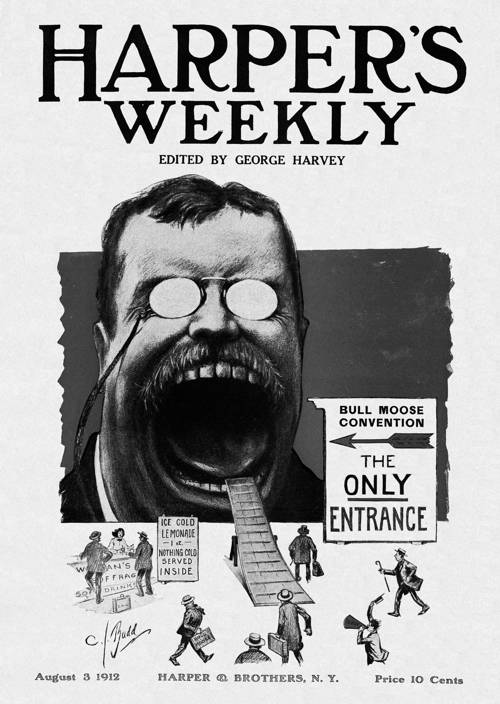

Published on the eve of the Progressive

Party National Convention, this Harper’s Weekly cover lampoons the

gathering as food for the gigantic ego of Theodore Roosevelt, the new party’s

soon-to-be presidential nominee. Delegates can enter the convention only

through the hot-air chamber of

Theodore Roosevelt campaigned actively

throughout the nation, including the South, and was received by enthusiastic

crowds everywhere. Because of the dignified manner set by his opponents, Roosevelt only vented a few personal attacks, referring

to “Professor Wilson” and concluding that Taft was “a dead cock in a

pit.” Roosevelt stressed that the

Democratic nominee’s antitrust proposals would actually allow untrammeled

liberty for large corporations. He also recycled Wilson ’s

past speeches and writings while a professor and Princeton

president, which disparagingly characterized labor unions as trying to get as

much as possible for doing the least work and which identified the march of

liberty with increased limits on government authority.

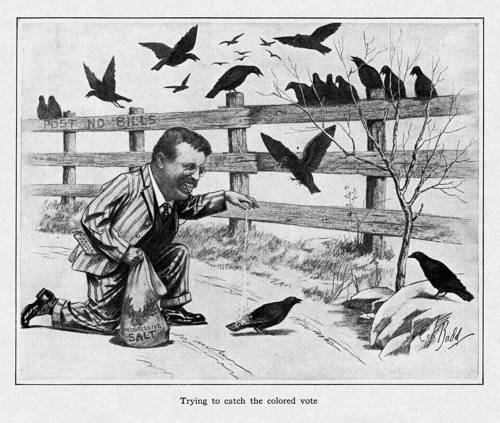

According to folklore, putting salt

on a bird’s tail allows you to catch it. In this Harper’s Weekly

cartoon, presidential nominee Theodore Roosevelt applies the method in an

attempt to capture blackbirds, which represent the black vote. The bull moose on the salt bag is a symbol of his Progressive

Party, and the “Post No Bills” warning on the fence is a pun referring to

President William (Bill) Howard Taft,

In 1912, some black voters

looked to the new Progressive Party as a possible political alternative to

Republican indifference and Democratic hostility. However, the Progressive

Party National Convention in August was a disappointment. With

In 1904 and 1908, the Socialist Party received slightly less than 3% of

the national vote. Although the total was down a fraction in the latter

contest, many Socialists agreed with their presidential nominee, Eugene Debs,

that 1912 “is our year.” Between 1910 and 1912, the party elected over

1200 public officials, including Congressman Victor Berger of Wisconsin

A 1912 almanac (calendar) printed by the Socialist Party has the months of the year bordered by quotes from Debs such as “I’d rather vote for what I want and not get it, than for what I don’t want and get it.” The measure of Debs and the Socialist Party is not in vote counts alone. A cartoon from the same 1912 campaign portrays the competition for progressive ideas by the parties, ideas such as voting rights for women, restrictions on child labor, and workers’ right to organize unions. It is highly doubtful if the Republicans and Democrats would have been giving at least lip service to such progressive ideas as early as 1912 had not the Socialists been popularizing these ideas since 1900. In the cartoon just mentioned, Debs is shown skinny dipping, and sees Teddy Roosevelt making off with his clothes.

From a Debs speech:

“The Socialist party knows neither color, creed, sex, nor race. It knows no aliens among the oppressed and downtrodden. It is first and last the party of the workers, regardless of their nationality, proclaiming their interests, voicing their aspirations, and fighting their battles.

It matters not where the slaves of the earth lift their bowed bodies from the dust and seek to shake off their fetters, or lighten the burden that oppresses them, the Socialist party is pledged to encourage and support them to the full extent of Its power. It matters not to what union they belong, or if they belong to any union, the Socialist party which sprang from their struggle, their oppression, and their aspiration, is with them through good and evil report, in trial and defeat, until at last victory is inscribed upon their banner.

Whether it be in the textile mills of Lawrence and other mills of New England where men, women and children are ground into dividends to gorge a heartless, mill-owning plutocracy; or whether it be in the lumber and railroad camps of the far Northwest where men are herded like cattle and insulted, beaten and deported for peaceably asserting the legal right to organize; or in the conflict with the civilized savages of San Diego where men who dare be known as members of the Industrial Workers of the World are kidnapped, tortured and murdered in cold blood in the name of law and order; or in the city of Chicago where that gorgon of capitalism; the newspaper trust, is bent upon crushing and exterminating the Pressmen’s union; or along the Harriman lines or railroad where the slaves of the shops have been driven to the alternative of striking or sacrificing the last vestige of their manhood and self-respect in all these battles of the workers against their capitalist oppressors the Socialist party has the most vital concern and is freely pledged to render them all the assistance in its power.”

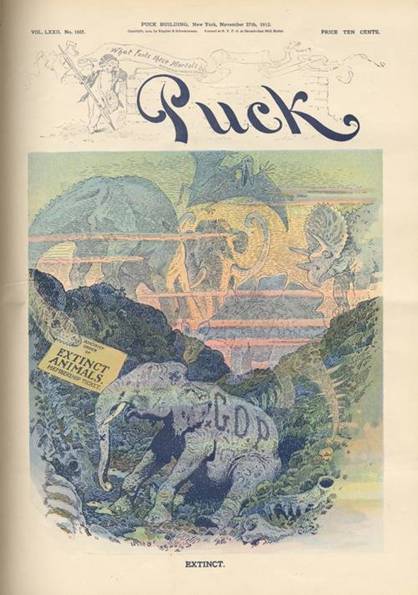

This cover of Puck, the Democratic humor magazine,

suggests that the 1912 election may mean the extinction of the Republican

Party. Although bitterly divided in 1912 between conservative and party

regulars behind William Howard Taft and progressives behind Theodore Roosevelt,

the party soon regained its former strength. While narrowly winning reelection

in 1916, Democrat Woodrow Wilson did not receive a popular majority. He

defeated Republican Charles Evans Hughes 277-254 in the Electoral College,

winning 49% of the popular vote to 46% for Hughes and 3% for Socialist Allan

Benson. Republicans steadily gained seats in the Congressional elections of

1914 and 1916, retook control of both the House and Senate in the 1918

elections, and won the presidency under Warren G. Harding in 1920.

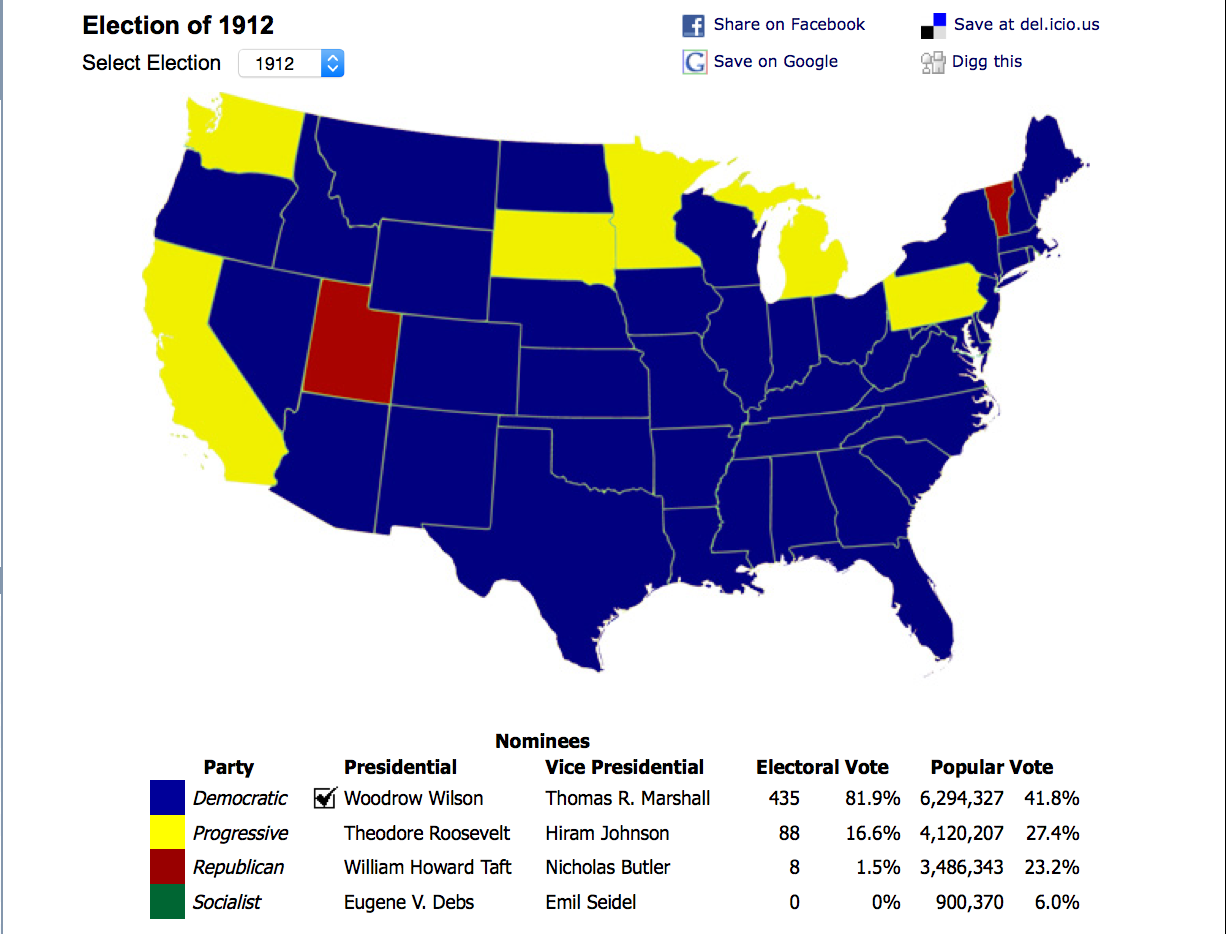

Results:

WW’s biggest wins are S Carolina (96%), Mississippi (89%), Louisiana (77%), Georgia (77%), Texas (73%); TR’s are South Dakota (50.5%), California (41.83% to WW’s 41.81%--a difference of 174 votes out of nearly 678,000), Michigan (39%), Minnesota (38%), Maine (37%); Taft’s are Utah, NH, Vermont (all 37%), Conn. and NM (36%). Debs does best in Nevada and Oklahoma (16%), Montana (14%), Arizona (13%), Washington (12%).