100 Years Later The 1911 Triangle Fire

Saturday, March 25, 1911. The work week was ending at the Triangle Waist Company factory in Lower Manhattan, and the men and women who operated the sewing machines and cut the cloth were pushing away from their tables, with some anticipating a night on the town and all looking toward their one day of rest.

100 Years Later The 1911 Triangle Fire

On the eighth floor, flames suddenly leaped from a wastebasket under a table in the cutters’ area.

While workers frantically struggled with pails of water to douse it, the fire hopscotched to other waste bins and snared the paper patterns hanging from strings overhead.

The fire spread quickly — so quickly that in half an hour it was over, having consumed all it could in the large, airy lofts on the eighth, ninth and 10th floors of the Asch Building, half a block east of Washington Square Park.

In its wake, the smoldering floors and wet streets were strewn with 146 bodies, all but 23 of them young women.

In the 100 years since the Triangle shirtwaist factory fire, as it is commonly recorded in history books, the story has been told many times about the poor, largely immigrant girls who toiled long hours inside an overcrowded factory only to find themselves one early spring afternoon trapped in a firestorm on floors where exit doors may have been locked. At least 50 workers concluded that the better option was to jump.

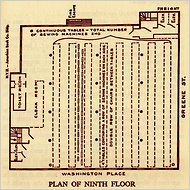

International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Archives, Kheel Center

The floor plan of the Asch Building’s ninth floor.

The ironies are many: The building was fireproof, and it still stands today. Like the Titanic a year later, it was considered state of the art, with conditions far safer than what existed before. The owners of the factory were themselves immigrants, but they became wealthy by employing newcomers at low wages at their shirtwaist factory, one of the largest in the city. And while two years earlier those owners had managed to withstand a 13-week industrywide strike aimed at achieving better conditions and union representation, the fire accomplished those goals and more.

On that Saturday 100 years ago, about 4:40 p.m., workers who had been perched at their machines since 8 a.m. were ending their week. As the whir of the sewing machines subsided and some workers headed for the cloakrooms for their hats and coats, flames were spotted in the wastebasket.

Workers unraveled a hose from a stairwell fixture, but no water came out. The building also had no sprinklers, nor had the factory held fire drills. The fire began to race across the 100-foot-long loft.

Workers rushed to an exit door leading to Washington Place, but it opened inward and some workers testified at a later trial that they first had to retrieve a key to unlock it. Still, most of the 180 workers were able to escape down the staircases.

As they fled, one Triangle supervisor on that fiery eighth floor placed a

warning phone call to the executive offices on the 10th floor, where the owners,

Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, were at work. Visiting were two of Mr. Blanck’s

young daughters and their governess, waiting for a promised shopping trip.

International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Archives, Kheel Center,

Cornell University The 10th floor of the factory. Of the 70 people on that

floor, all but two were saved.

International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Archives, Kheel Center,

Cornell University The 10th floor of the factory. Of the 70 people on that

floor, all but two were saved.

The 60 or so executives, pressers and packers and two children escaped through choking smoke and flames onto freight elevators or up stairs to the roof. There, a New York University law professor and his students in the taller, adjacent building lowered ladders — fortuitously left by painters — to pull them to safety.

But, in her alarm, the worker who had taken the call on the 10th floor never hung up the phone. That prevented anyone from calling to alert the 250 workers on the ninth floor. Only when they saw flames rising up the air shaft, incinerating tables where shirtwaists were examined for workmanship, did the seamstresses, cutters and support workers who were crowded among eight rows of sewing machine tables realize they were in danger.

Many of the 250 workers crammed the usual exit, a door on the Greene Street side of the building, where a supervisor nightly checked departing workers for any hidden shirtwaists or stolen scraps of lace.

Others, seeing the press of bodies, hopped from table to table to reach the Washington Place staircase diagonally across the loft.

There, a young man twisted the lock of the Washington Place door and screamed, “The door is locked! The door is locked!” according to workers’ testimony. Others tried to open it and also failed.

Dozens managed to make their way into the two freight elevators, where their

operators, Joseph Zito and Gaspar Mortillalo, returned again and again to the

burning floors, risking their own lives to save 150 people, according to “Triangle:

The Fire That Changed America,” a 2003 history by David Von Drehle.

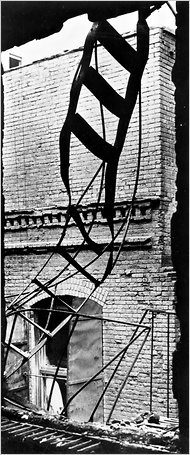

Brown Brothers The flimsy fire escape ladder.

Brown Brothers The flimsy fire escape ladder.

Some who could not crowd into the elevators attempted to slide down the cable or jumped or fell down the shaft, and soon the elevators stopped, one so weighed down by the crush of 19 bodies that it could no longer rise.

As hundreds watched from nine floors below on Washington Place and Greene Street, workers hung out of windows and climbed onto ledges, hoping to be rescued by fire trucks that had responded within minutes of the first alarm.

But when the ladders stretched only to the sixth floor, 30 feet below, and flames began to singe their hair and consume their skirts, many jumped, often in twos and threes — 54 of them altogether, by the count of William Gunn Shepherd, a United Press reporter who was first to the scene.

Witnesses reported seeing a man at a Washington Place window who, in a gallant effort to spare his co-workers from the licking flames, held out three women at arm’s length and dropped them, one by one, to their deaths. Then he kissed a fourth, released her to her death — and plunged to the sidewalk himself.

“They were all as unresisting as if he were helping them into a street car instead of into eternity,” Shepherd reported. “He saw that a terrible death awaited them in the flames and his was only a terrible chivalry.”

Workers who pressed onto the fire escape in a rear air shaft found their way

blocked by swinging metal shutters. Had they made it all the way down, they

would have found that it ended treacherously a full floor above a basement

skylight.

Brown Brothers Police officers and firefighters spent four discouraging hours

lowering shrouded bodies from the factory.

With so many people crammed onto the fire escape with nowhere to go, it collapsed. Two dozen bodies were later recovered among the broken glass below the air shaft on the basement floor.

As the sun set, policemen and firemen recovered the charred corpses, lowering some by block and tackle to the sidewalk to join the broken bodies of the co-workers who had jumped.

A parade of vehicles transported the bodies to the Charities

Pier on 26th Street, and there they were lined up in simple wooden coffins

for relatives to identify.

A parade of vehicles transported the bodies to the Charities

Pier on 26th Street, and there they were lined up in simple wooden coffins

for relatives to identify.

Tens of thousands showed up, the voyeurs and pickpockets mingled with grief-stricken

relatives who were seeking any telltale features — hair braids, shoes,

jewelry, gold teeth — so they could pick out their mothers, sisters,

fathers and brothers from among the scorched faces.

International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Archives, Kheel Center,

Cornell University At the 26th Street pier morgue, family members and friends

tried to identify their loved ones.

International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Archives, Kheel Center,

Cornell University At the 26th Street pier morgue, family members and friends

tried to identify their loved ones.

All but six were identified. On the day the city buried them in a shared grave at the Cemetery of the Evergreens on the border of Brooklyn and Queens, the grief and anger of the city spilled out onto the downtown streets in a somber, rain-soaked funeral march for those “unknowns.”

Hundreds of thousands made their way on routes from the north and south, meeting in Washington Square Park, where on a sunny Saturday a few weeks earlier, the clang of fire bells had shattered the genteel calm. Police officials, worried the crowd would erupt in a frenzy, diverted the marchers away from the Asch Building, to continue their procession uptown.

For nearly 100 years the names of those six remained unknown — until

a persistent researcher, Michael Hirsch, ended the mystery, just in time for

the centennial of their deaths.