1503

Encomienda system first instituted, by Columbus in the Caribbean. This link also explains the repartimiento (see 1542, 1549).

1511

Taínos Rebel in Puerto Rico. Angered at forced labor, slavery, and mistreatment under the encomienda system, Taínos attack the Spaniards, killing about 200. In retaliation, the Spaniards burn Taíno villages and brand an F—for Ferdinand, the Spanish king—on the head of every Taíno captured.

In a fiery Christmas Eve sermon, the Spanish priest Antonio de Montesinos denounces the encomienda system and condemns Spain's taking of American land and indigenous labor as robbery and slavery. It represents the first time a Spaniard in the Americas speaks out against injustice and for Indians. In the audience is Bartolomé de Las Casas, an encomendero who in the following year will be ordained as the first Catholic priest in the Americas.

1519

Cortés lands in Mexico

1521

Cortés conquers Mexico; first Franciscan friars walk into Mexico City. They believe that conversion of the natives marks one of the final chapters in the history of Christianity and will bring on the end times. Cortés bans human sacrifice but does not ban other expressions of indigenous religious belief for security reasons.

1525

Spanish close native temples, which have been “in full operation” since 1521, according to historian Patricia Lopes Don. Franciscans begin campaign of mass baptisms.

1528

Concordia of 1528: in Spain, Spanish crown will still use Inquisition to persecute crypto-Jews (conversos whom it thinks are secretly still Jewish) but will not persecute moriscos (allegedly converted, but possibly not, Muslims) until the third generation after conversion, “since it would be impossible for them to shed all their customs at once.”

Will natives in Mexico be treated more like former Jews or more like former Muslims? A total of 4 Indians are prosecuted in the 1520s, usually for keeping concubines or swearing, by passing friars whom the Bishop of Santo Domingo has endowed with inquisitory powers. Polygamy and pagan feasts are everywhere, according to critics, who blame the Franciscans’ mass baptisms for pasting a coat of Christianity atop unchanged native customs.

1530

Queen releases a royal order mandating each Indian leader choose only one wife and abandon the rest; friars wage a public campaign of forced marriages and floggings of leaders who defy the law.

1531

Virgin of Guadalupe appears to Juan Diego, according to tradition.

Historians suggest that this date is actually invented later; an indigenous artist created the image in the 1550s (though the first written description of the cult of the Virgin is not until 1648, the author noting that “I searched for papers and writings regarding the holy image [from the 1530s], but I did not find any”), a cult grew around it, and it was then legitimized by creating an earlier date of origin. (Some later appropriations of the Virgin.) This is actually fairly common in the pre-modern world; other famous forgings, or later creations of originating documents, include the Donation of Constantine and the Pact of Umar.

Among the problems with the story: no one knows who Juan Diego was, where he lived, or which class he belonged to. No one has found any proof of his existence. The records of the Archbishop at the time contain no mention of the apparition at all. One of the first recountings admits that no sources exist. For some, these were a problem. One historian wrote in the 18th century that "the forgetting of such a great benefit that the Empress of Heaven did for our America, and especially for Mexico, was certainly something worthy to be pondered." 17th-century apologist Francisco de Florencia, a Jesuit priest, explained in La Estrella del Norte de Mexico [1688] that actually lack of documentary evidence proved the story's divine origin: "it seems that it was not just human carelessness, but also the foresight of divine providence that for us the only proof of those signs should be tradition."

This question has been remained controversial for over a century. Some scholars have argued that oral tradition is all that matters, whether or not the story is true ("the question as to whether the apparition did in fact occur is inconsequential: for those who believe, no explanation is necessary"), while others think that we should accept only that which is verifiable. They also wonder how to prove an oral tradition existed in the first place, since one of its defining characteristics is lack of written records. A movement to beatify Juan Diego began in 1888, picked up speed in 1979, ran into some difficulties inside the Vatican in the 80s ("this business of Juan Diego, there is nothing," one monsignor told a Mexican Monsignor. "The Virgin of Guadalupe was a myth which the missionaries used for the evangelization of Mexico, and Juan Diego did not exist"), and then succeeded. In 1990, the Pope recognized the cult of Juan Diego, made his feast day Dec. 9, and declared him "blessed since the moment of his death."

When the Abbot of Guadalupe declares the story a myth ("Juan Diego is a symbol, not a reality") in a 1995 interview, it creates an uproar. He is called a "traitor to the church" and accused of "wounding all Mexicans" by the Archbishop of Mexico City. A spokesman for the archdiocese claims that "anything that goes against Juan Diego and the Most Holy Virgin of Guadalupe affects all of us, because it is part of our very own identity." In 1999, presidential candidate Vicente Fox weighs in, saying that questioning the story "is to go against the current, to go against an entire people."

In 2002, Juan Diego is formally canonized. The Virgin remains a resonant symbol for artists. She is also politically controversial.

1533

Julián Garcés, bishop of Tlaxcala, protests Spanish treatment of natives and denial of their ability to receive church sacraments; one friar denies absolution to encomenderos; de las Casas protests Spanish slaving expeditions to South America, and the resulting captives are freed.

1536

Friars found Colegio Imperial de Santa Cruz de Santiago de Tlatelolco, intended to teach natives European culture, Latin, Christian theology and prepare them to enter the seminary; Spanish crown authorizes Bishop Juan de Zumárraga of Mexico City, who had presided in a witch trial in Spain, to establish an inquisition. He holds 19 trials for paganism or idolatry, 1536-43.

Trial of the alleged sorcerer Martin Ocelotl (jaguar), who had been forced in 1533 to marry one of his wives, publicly oppose bigamy, and declare “to the entire village” of Texcoco that he had given up his old ways. Now he is accused of bewitching people; turning himself into a lion, tiger, or dog; healing people by rubbing green stones on them; praying to pagan gods; claiming he is immortal; being able to “call my sisters” and make it rain; and saying and doing “many other things that were contrary to our sainted faith.” He claims that Christian missionaries “had long claws and great fangs and other frightful features,” but that he would reduce them to pulp.

The process of research in the case uncovers Martin’s great wealth and ties to indigenous leaders throughout the valley. (Ocelotl himself, according to later historians, appears to be a local shaman trying to build a reputation through claims to traditional skills and language rather than a full-bore practitioner.) Though Ocelotl pleads that he is innocent because he feels he has done no wrong, he is publicly humiliated and banished to Seville, where the Inquisition can keep an eye on him.

1537

Pope Paul III issues Sublimus Deus, which angers the Spanish King, who sees it as an incursion on his rights.

1539

Don Carlos Ometochtl (or Ometochtzin) of Texcoco, supposedly a convert to Christianity, is burned at the stake for not just practicing, but evangelizing for, Aztec religious practices. He says he turned away from Christianity after the trial of Martin Ocelotl and makes remarks like, “who are those that undo us and disturb us and live on us and we have them on our backs and they subjugate us? …No one shall equal us, that this is our land, and our treasure and our jewel, and our possession, and the Dominion is ours and belongs to us.” When the Council of the Indies learns of this punishment, they take away the bishop’s powers of inquisition (to find and punish heretics) for the remainder of his life, until 1548.

1540

Debates in Spain among Spanish religious leaders: how to punish those who have treated natives badly? How to best instruct Indians in Christianity? How to guarantee fair treatment of natives?

1542

New Laws abolish future encomiendas, reduce the estates of those with too many encomiendas, and ban enslavement of any kind or physical mistreatment of natives, who are now to be subjects of the crown, not of individual encomenderos; natives in Cuba, Santo Domingo, and Puerto Rico are to be treated as Spaniards there are. When encomenderos die, their lands revert to the crown.

Bartolomé de las Casas publishes A Very Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies; conquistadors, particularly in Peru, rebel against the New Laws; Fray Alonso de Castro’s Utrum Indigenae Novi Orbis argues that natives should receive higher education.

1543

Bishop Zumárraga’s Conclusión exhortatoria argues that the Bible should be translated into native languages so that any literate native can understand Christianity. Council of the Indies revokes Zumárraga’s inquisitorial powers, Francisco de Nava, bishop of Seville, explaining that while he understood the execution of Don Carlos “in the belief that burning would put fear into others and make an example of him,” the Indians “might be more persuaded with love than with rigor”; when King Philip II formally establishes the Inquisition in New Spain in 1571, he specifically prohibits trials of indigenous colonists.

1549

1563

King introduces repartimiento

In the 1550s, the Crown proceeded to regulate the tribute that could be received by the lords from their vassals. Even more significant were the reassessments made by Inspector General Valderrama in 1563. Valderrama incorporated the mayeques (people conquered in pre-Hispanic times who had become tenant farmers or sharecroppers on lands they previously owned) of the native lords in tributary registers, while also including the principales (Indian leaders, the nonruling nobility), who until that time had been exempt from paying taxes. The tax adjustments made by the inspector general led to a wave of protests on the part of native lords and principales.

1632

King abolishes repartimiento

1648

Sor Juana born

1668

Sor Juana enters Convent of San Jerónimo

1694

Under pressure from church hierarchy, Sor Juana sells her books and musical and scientific instruments

1712

Tzeltal Revolt: In June, in Cancuc, in the Maya highlands of Chiapas, 13-year-old María López, daughter of the church's sacristan, sees and speaks to the Virgin Mary, a beautiful white woman, on the outskirts of town. The Virgin tells María that she is here to help the Indians and that they should build her a shrine. Her mother urges her to proclaim the miracle to the pueblo, and her father goes with her to the site and puts up a cross. The village then builds a chapel on the site, where, according to María, the Virgin continues to visit and speak with her.

The parish priest denounces the miracle as the work of the Devil and has María and her father lashed 40 times each, but the townspeople defy the priest and continue to worship at the new shrine. Local officials celebrate rather than denouncing the miracle and are imprisoned, but pilgrims start to make their way there anyway. Two months later the local officials escape from prison and make their way back to town. Townspeople move statues of the Virgin, St. Antonio, and St. Pedro to the new shrine and ordain new priests.

In August, 21 pueblos in the highlands proclaim "Ya no hay Díos ni Rey" ("now there is neither God nor King") and rise up against the government. They proclaim that their sect represents the one true church (they call the Spaniards "Jews," "demons," and "devils"), march on local Catholic churches, execute the officials defending them, and attack symbols of authority throughout the region, including Spanish estates. 5000-6000 troops fight for the rebellion at its height. The rebellion is mostly put down by November and finally pacified by February, with more than 65 rebels being executed, though María remains at large until 1714, when she dies in childbirth, and her father until 1716, when he is caught and executed.

1746

by general oath, the church declares the Virgin to be patron of all New Spain

1761

Conflict arises when Bourbon ministers meddle with religious practice and ritual, not belief.

Antonio Pérez, an Indian, is reported to the Inquisition by priest Domingo de la Mota. 64 Indians are subsequently arrested for “idolatrous practices” in Chimalhuacán, in Chalco. Pérez declares himself a “high priest,” leading worship of, in Mota’s words, a figurine “made in wood in the shape of a woman…seated on a chair, her shoulders covered with a shawl…and instead of a skirt she wore a yellow altar pallium [a band typically conferred on Archbishops by the Pope].”She was known to devotees as “Our Lady the Virgin of the Lily, the Palm, and the Olive,” but she’s not the Virgin because, Mota says, “her breasts were naked and monstrous and her face resembled more that of a man than of a woman.” Pérez said that the established church was at fault: penitents were poor because “they went to church which was hell,” “listened to the priests, who were devils,” and “believed in the god of the priests, who was false.” It would be better to “commend themselves to drunkards” than to priests. He also celebrates Mass, hears confessions, administers baptism and the Eucharist, witnesses marriages, and insists that worship be of the one true God—who was NOT the God of the priests. He is accused of paying local Indians to baptize babies in pigeon's blood rather than holy oil.

Several Indian revival movements resist the church and deny that they have a Christian identity. A group of Indians in the Sierra del Pueblo in possession of an arsenal of machetes, knives, and pistols argues that the God of the Spaniards was the devil, that Catholic priests are demons, and that the Virgin has lost her powers.1784

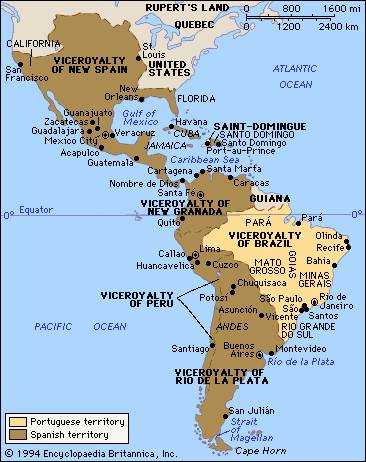

viceroyalties in the Americas

map of the governmental structure of New Spain

2007

Pope Benedict gives controversial speech claiming that New-World residents had been waiting for Christianity: “what did the acceptance of the Christian faith mean for the nations of Latin America and the Caribbean? For them, it meant knowing and welcoming Christ, the unknown God whom their ancestors were seeking, without realizing it, in their rich religious traditions. Christ is the Saviour for whom they were silently longing….In effect, the proclamation of Jesus and of his Gospel did not at any point involve an alienation of the pre-Columbian cultures, nor was it the imposition of a foreign culture.” Responses are not kind.